Getting to know ‘Reform curious Labour voters’

Can Labour hold together its election winning coalition?

About nine months ago, the UK Labour party won a sweeping victory at the 2024 general election.

I mention this only because you could be forgiven for having it slip your mind.

The return of Trump to the White House and a spike in support for Reform has quickly led Westminster back to one of its favoured topics: the unstoppable rise of the radical right.

This is beloved territory in part because it allows everyone to resume doing what they like best: the conservative right get to continue shaping the media agenda; the liberal left get to feel bad about themselves.

An important piece of leverage here is the spectre of the left behind voter. Typically living in a Red Wall seat, Labour all their life but - increasingly disillusioned with the party’s metropolitan pre-occupations – now drifting to Reform.

How real is this pen portrait? How direct a threat do Reform pose the Labour coalition and how might the government balance these switchers with other parts of its coalition?

This among other things is covered in some new research I have out today via Persuasion UK, featuring in today’s FT. It’s the product of about four months of research spanning focus groups, polling and experimentation.

There is a lot of graphs and data in the full report – please check it out - but i’ve tried to condense what I’ve found and what I think it means below.

Part 1: putting Labour to Reform switching in perspective, quantifying it – and a look at tactical voting dynamics

To properly understand this phenomenon, it’s important to place it in context.

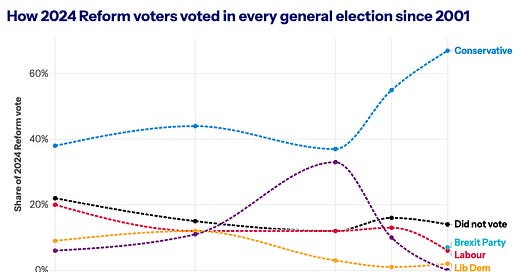

The first thing – and I really cannot emphasise this enough – is that historically speaking Reform voters are not ‘Labour’s lost voters’. In fact, looking at British Election Study (BES) data, 74% of Reform 2024 voters did not vote Labour in a single general election between 2005 and 2019 (and this is only as far back as we have data).

And no, these numbers do not shift all that much in electoral battlegrounds.

Instead, Reform voters can largely (of course not exclusively) be thought of as historic anti-Labour voters who have bounced around between UKIP, the Conservatives, non-voting and even the Lib Dems. Boris Johnson consolidated them in 2019, only for family disputes on the right to see things unravel in 2024.

Ok, so that’s the past. But what might happen in this Parliament?

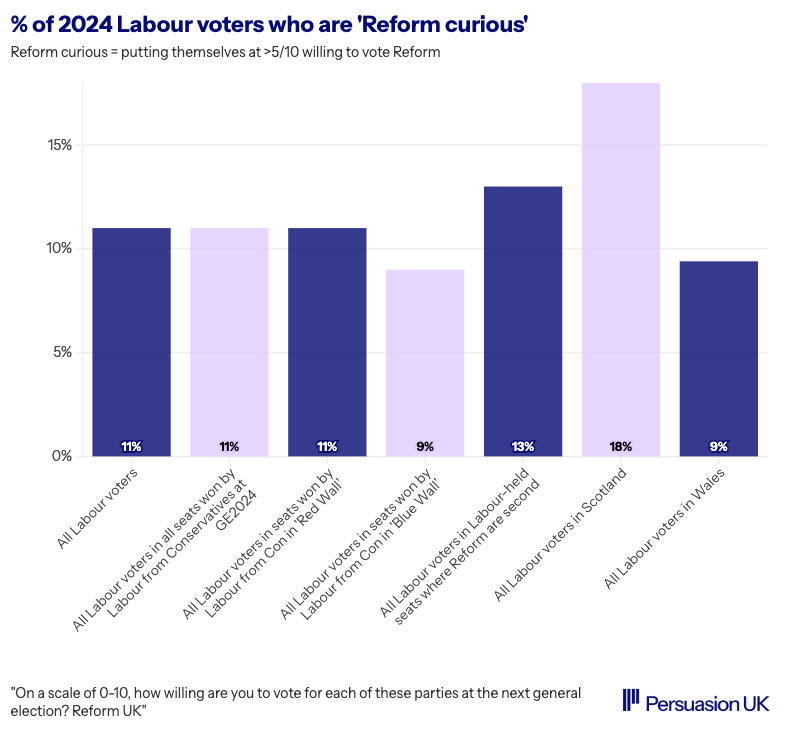

Right now, there is about 11% of the Labour 2024 vote who say they are open to switching to Reform or have done so. These are what we can call ‘Reform curious Labour voters’. Their number varies a bit by battleground, but not really. The only real outlier is Scotland, where they clock up at 18% of the Labour vote.

Actual Labour to Reform switching represents around 7% of Labour 2024 vote right now, again only notably higher in Scotland (my best guess on why: Labour’s vote in Scotland is older and had more tactical voters in it).

These numbers absolutely matter, not least because in Labour-Reform battlegrounds switchers ‘count double’.

They also, though, need to be seen alongside wider electoral currents.

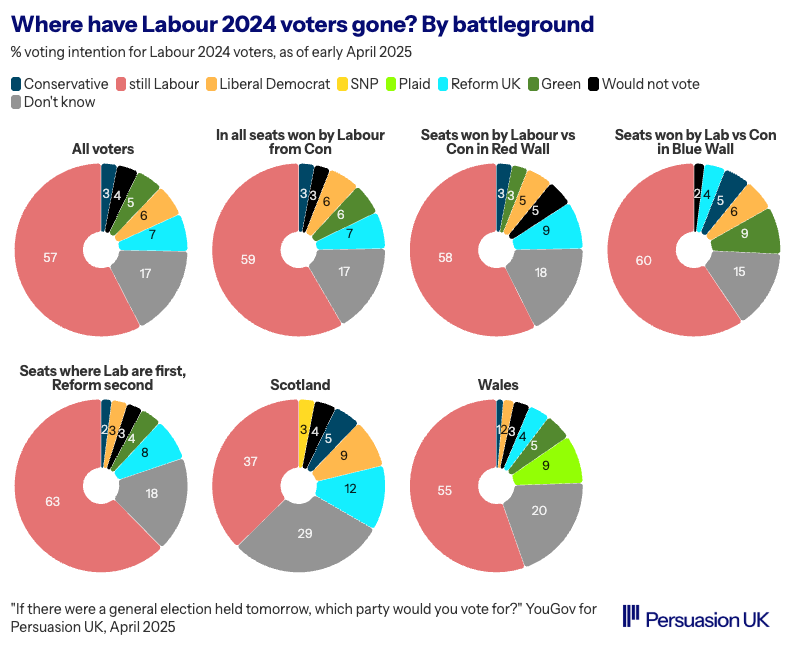

Under the surface, most of what accounts for Labour’s dip in the polls is its vote flaking off to the left or else going ‘don’t knows’.

The first of these is a particularly big vulnerability. Indeed, ‘Green curious’ or ‘Lib Dem curious’ voters comfortably outnumber Reform curious Labour voters even in the Red Wall (!). They are an especially big deal, though, in the Blue Wall seats Labour won across swathes of the South of England especially.

Not all of these voters will go on to switch, of course, but it remains true that the ceiling on left defectors is just higher (a case in point: MRP analysis shows that - all else being equal - if Labour lost every Reform curious Labour vote, it would lose 123 seats; if it lost every Green curious Labour voter it would lose 250 seats).

The daftest thing for Labour to do at this point would be to dissolve into factional bunfights over which of these groups matter more or less. The boring truth is they all do, i think; both sides of the coalition are essential when you win on 33% of the vote and the skill will be in keeping them together not trading them off. We’ll come back to this.

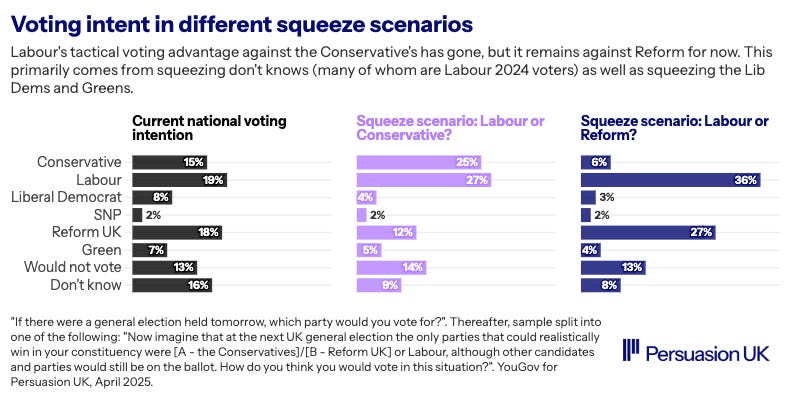

For now though the biggest threat of Reform in this Parliament is tactical voting among 2024 anti-Labour voters, not direct switching.

On this score, the other thing we find is it is currently very useful for the government for the next election to be framed as Labour or Farage – since it helps them squeeze back left-leaning voters especially, plus a small slice of the Tory vote. This is a sign that the ‘love them or hate them’ nature of the Reform brand carries risks as well as benefits.

Part 2: understanding the demographics and values of ‘Reform curious Labour voters’ – and how they differ to other voter groups

Having isolated Reform curious Labour voters, we can start to look at who they are – and who they are not.

As you’ll see in the report, demographically they look pretty similar to the wider Reform vote – and very different to the Labour one. Older, overwhelmingly working class and non-university educated. This bit of SW1 folklore is true, at least. The only interesting wrinkle is housing, where they are twice as likely as Reform voters to be social renters.

Beyond that, the main thing they share with Reform voters is a very solid social conservatism. As you can see below, they are just generally closer to Reform on cultural divides than the rest of the Labour vote. That said, they hold such views less intensely than core Reformers.

On economics, meanwhile, we see the flip reverse. Suddenly, the Labour coalition is not as spread out, and Reform curious Labour voters find themselves on the other side of the argument from their potential Reform bedfellows.

In short, this is a classically cross-pressured voter: socially conservative, economically populist, disaffected. They dislike asylum seekers but also water CEOs and landlords, that sort of thing.

At the moment it’s the former which is making them Reform curious. The issue of immigration tops their reasons for considering Reform. When you dig into it, in practice this is overwhelmingly about asylum - small boats and hotels – not regular migration.

It’s equally important, though, to note what does not float their boat.

This is just a much less all-round cranky kind of voter than the standard Reform voter. Yes they are annoyed on asylum, but broadly they don’t buy into the wider set of Reform hobby horses. There’s a clue to this in their media consumption: only 16% get their news from GB News, compared to 37% of the Reform vote at large.

Probably the best example of knock-on to issue attitudes concerns Net Zero. Reform’s base are now consistently hostile to the clean energy transition. But Reform curious Labour voters are just not. Reform voters blame it for rising energy bills, Reform curious Labour voters do not. Though they prioritise climate and the environment much less than the wider Labour vote, Reform’s hostility to it does very little work in pulling anyone over to them from Labour.

On the other side of the coin, we found low-level anxiety among Reform curious Labour voter’s about ‘extremism’ and Farage’s proximity to Trump in particular. The government’s own handling strategy for the US President forecloses them from ‘doing a Carney’ on this for now, but it remains a bruise for Reform - and an issue which generally splits their vote.

Part 3: how Labour might unite Reform curious Labour voters with other swing groups?

So is there a way for Labour to thread needle with these voters and its increasingly fractious base?

To get underneath this, and try to surface the real trade-offs, I set up what’s called a conjoint experiment.

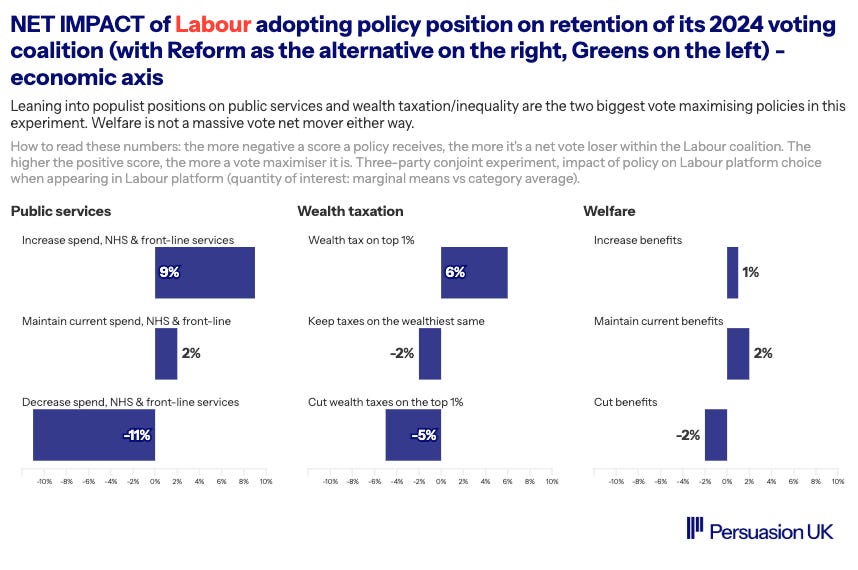

1,000 Labour 2024 voters were invited into an experiment. They saw a Labour policy platform, a Reform platform and a Green platform. These platforms are made up of random positions on six key areas: immigration, asylum, Net Zero, public services, wealth taxation and welfare. We keep the Reform and Green platforms the same (in positions we know they have), but we vary the Labour platform for reach respondent randomly.

We then ask people who they’d vote for in different scenarios. Below is one example variation seen by one respondent.

In the analysis phase, we can see which of the many possible Labour positions most fractured the Labour coalition – sending voters to Reform or the Greens – and which, if any, kept Reform and Green curious Labour voters in the tent at the same time.

Each policy is assigned a percentage value: TL;DR the more net positive the value, the more it increases the probability of Labour voters sticking with the party over Reform or the Greens. The lower it is, the more it decreases that probability and drives defection in one or both directions.

Ok, so what do we see?

For sure, limited political room for manoeuvre on hot button cultural divides like asylum and migration. Very liberal positions here see vote loss to Reform, but very authoritarian ones tend to cancel themselves out electorally, losing to the Greens what they retain from Reform. Boring moderation is the order of the day here.

But it’s the economic axis where hope probably lies for Labour. If there is any magic sauce, it is in taking these cautious positions on culture topics and combining them with more adventurous – or even populist – positions on economic fights. The top two best performing policies, keeping both Reform and Green defectors onside simultaneously, were significantly increasing funding for the NHS and front-line services, and a wealth tax on the top 1%.

A quick word on Net Zero here too.

Obviously it is really important any policy in this area does not noticeably drive up cost or inconvenience to consumers. But at a signalling level at least, confidence in this area appears to be a ‘free hit’. It keeps Green/Lib Dem voters inside the tent, for whom it is disproportionately salient, without costing anything with Labour/Reform leaners - who basically don’t care much either way. Being seen to go backwards on it is damaging for the inverse reason.

So what to take from all of this, and what not to?

I personally would not fixate too much on the policy specifics (please no fighting about wealth tax designs in the comments).

What it is more useful for is telling us is about signals – the strength of signalling - and dividing lines.

And on this, all evidence I’ve seen is fairly consistent. If Labour wants to keep its existing coalition together, it is questions of economic justice, redistribution and the role of the state that binds it together – and culture which tugs it apart. This dynamic is the reverse of what we saw in the 1990s.

Utilising this insight, though, has to be about more than programmes – especially given the way the attention economy increasingly works. It’s about actively seeking conflict on these economic left-right fights; creating them, welcoming them when they come, basking in them until voters notice the choice on offer. This is actually what they can learn from Trump on, not much else.

It’s combining this emotionalism (or populism if you prefer) with some actual deliverism – actual improvements in public services especially – and then making the next election Labour vs Farage which is likely the ideal path, in my view, as hard as all of these things are to pull off.

The odd thing is that government does arguably have an existing agenda they could start to build such a strategy on. They massively increased taxes on the rich and big business to rescue the NHS at Budget; workers rights, renting reform, etc.

But they have tended to run away from fights on these issues, preferring instead to insist that nobody will lose out from them. As a result, I’d argue only the losers of these policies know or care about them.

Very likely this comes back to tensions – or lacunas – in their theory of growth, and resulting jitters about investor and bond market sentiment. But it’s still a missed opportunity in my view.

--

Just quickly…

One limitation is worth flagging here, namely that I have assumed Labour actually want to ‘get the band back together’.

But what if they don’t. What if instead of re-building its 2024 coalition, it wanted to re-make it slightly?

One alternative path might be just writing off either Reform curious Labour voters or Lib Dem/Green defectors entirely and try instead to win other groups over – perhaps anti-Reform Conservative 2024 voters.

I am not sure the numbers or issues really exist to do this on, but it’s possible.

Either way, they need to settle fairly sharply on who they want to win next time and how. On both of these questions there seems to be multiple theories in evidence right now, all slightly in tension with each other, contributing to the slight sense of formlessness and managerial drift that sometimes characterises the government’s general oeuvre.

Of course, this is also because governing is just very hard – harder than making graphs – especially at the moment.

Nevertheless, it is that drift above all which is encouraging nervous liberals and the media to feel that Reform’s rise is pre-destinated. Through this lens, the current administration is nothing more than a kind of freak Weimar-style interregnum.

But none of these things have to be true. Reform have massive weaknesses - and to be in government is to hold perpetual serve. If Labour use both wisely, there is still time to get things right.

~ @SteveAkehurst

~ @SteveAkehurst.Bsky.Social

The full research is here! Thank you to the many many people involved in helping with it.

Excellent, as ever!

Super interesting. Thank you for putting this together. Most of the reform folks I know (Mindlands town) are generally older (50+ and voted Conservative most recently, Labour historically. More than of a few of those thing Farage is a elite/wolf in sheep's clothing type, those who don't would never vote Labour anyway. The younger generation are a bit of a worry for me, but I also cant really see their turnout increasing much in the coming years.