Greenwashing: a good problem to have?

Of course we should hold business to account, but we should probably worry less about their ability to deceive the public

In the untidy world of issue campaigning, many internal debates come back to a familiar set of dilemmas. One of these concerns coalition building. As unusual partnerships are formed made in the interests of alliance building, or even fundraising, sometimes the question gets asked: “are we co-opting them, or are they co-opting us?”

One area that gets a lot of attention in climate is ‘greenwashing’. The most conventional argument is that large companies piggy back off public concern to promote themselves as environmentally friendly in spite of their behaviour. A proliferation of soft-focus green ads and initiatives about sustainability are designed to deceive us, it’s argued, with many pressuring regulators to take action.

A modern variation on the theme is that these actors intentionally ‘individualise’ climate action in their campaigns. That is, they disingenuously promote personal responsibility – individual behaviour change - to deflect attention from collective solutions that may hurt their profits.

A motif to this story is that BP created the concept of a ‘carbon footprint’.

It’s hard to truly assess intentions here. Clearly for some, most likely companies whose core business is fossil fuels, green initiatives will be bad faith. For the majority it’s less obvious. Most large organisations are not inherently one thing or another, but a melange of competing interests, incentives and schools of thought all vying for supremacy. The world is chaos.

But away from that messiness, it is easier to evaluate the impact of such efforts on public opinion and behaviour.

Of course deception, where it actually exists, is bad and should be called out on its own terms. But I’ve simply never seen any evidence that ‘greenwashing’, as alleged, really works to hold back climate action with the public. If anything, probably the opposite is true.

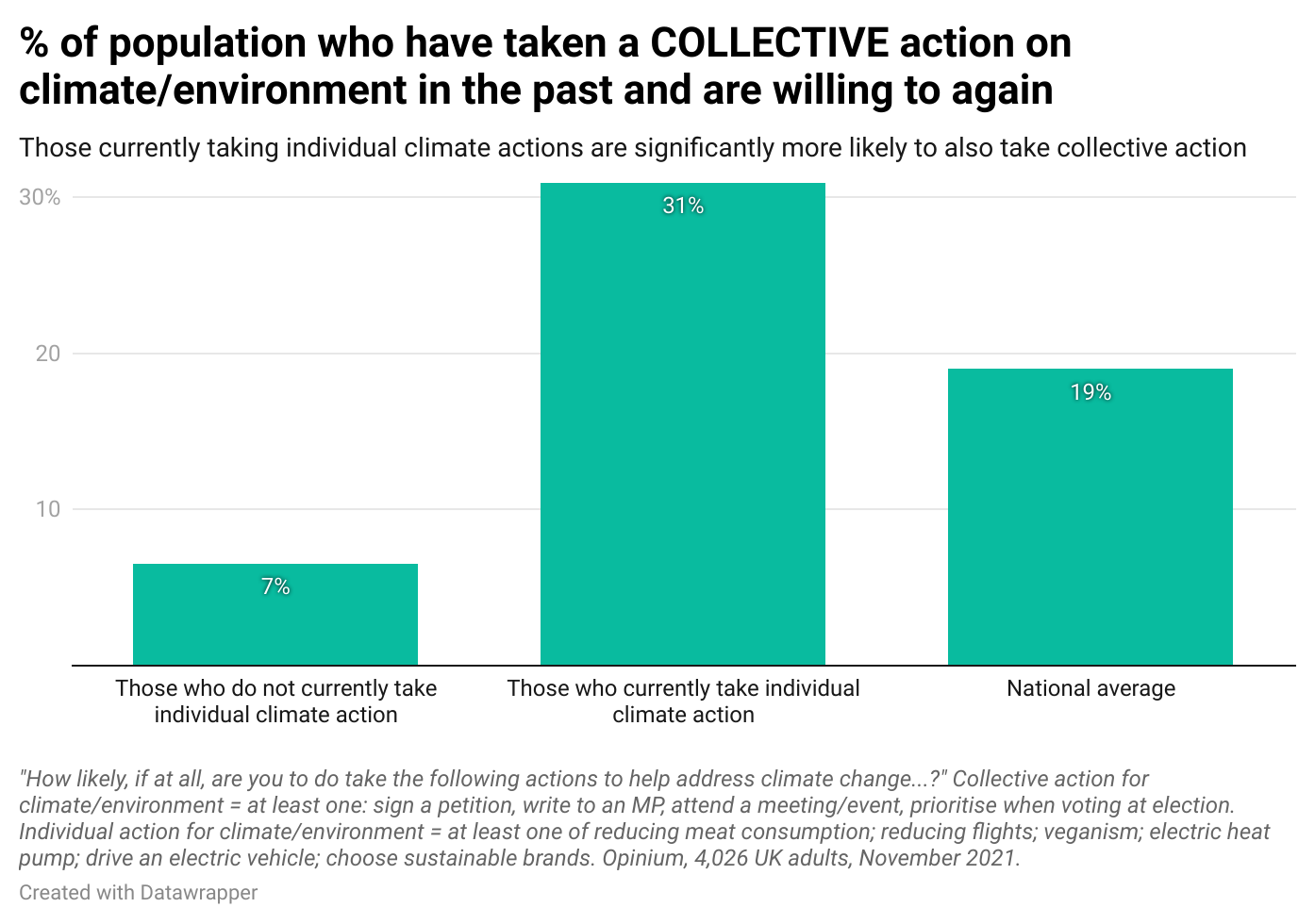

Take for example one recent survey. It shows that those who take personal action (e.g. reduce meat consumption, shop sustainably) are actually significantly more likely to have also taken a collective action (e.g sign a petition, attend a protest). They also are more likely to think the government should be doing more on climate.

Looking at the same data from a different angle, in graph 2, we can see these are largely the same people doing both.

If the zero-sum theory of mobilisation truly held, we would expect to see the reverse of this, as individual behaviour sates people’s appetite for action. Instead, one is the gateway to the other. This corroborates Climate Outreach’s work in this area.

It’s possible that BP – or some expensive PR consultant in their pay – did indeed think they were being clever in promoting individual climate action. It’s just that if that is the intention, it doesn’t work. Quite the opposite.

Moreover, per the below, there’s no evidence that the likes of HSBC and others positioning themselves as green has done anything much to boost trust in big business as voices in the climate debate - at least with the public.

Even at a consumer level, studies and polling suggest consumers are smarter than to let green initiatives influence their purchasing choices, unless they judge them to be genuine. Ordinary voters have better bullshit detectors than they are often credited with.

What might explain all this?

Pre-COP UK focus groups by the excellent More in Common tell us something here.

At around 23 mins, participants are discussing plastics - something that has itself been a gateway to climate concern for many voters. When the moderator probes, they tell him they still support regulation promoting environmentally friendly action even if they themselves take action voluntarily. Good old fashioned British curtain twitching seems to play a role. Essentially, ‘I can be trusted to do this myself, but others can’t’. The parallel with Covid rules is obvious.

Indeed both personal and individual action is usually just a function of salience – that is, thinking climate is a priority above other issue. Taking or supporting one action builds momentum for others, rather than lessen it, as it becomes a bigger part of someone’s sense of self.

In this regard, green focused ads and initiatives may actually help. For less engaged votes, climate competes for attention with multiple other issues – that’s why it ebbs and flows with the news agenda so much.

While seemingly doing little to really serve the interests of companies, these ads may have the effect of boosting the salience of climate by reminding voters, via subconscious social queues, that the issue is important.

There are studies which back up this theory. One foundational piece of work (downloadable here) by researchers at Stanford University found:

In a controlled experiment, telling people that 30% of Americans are trying to reduce meat and that this number was increasing (‘dynamic norms’) had a statistically significant effect on their own willingness to reduce meat consumption.

In follow-up experiments, this translated into the real-world settings.

The thread that ties this together is social norms: among those with no firm ideological view either way, social signals and pressures – especially indicating that attitudes are changing - can be important in boosting salience and thus action. This is why the ‘black squares’ of the BLM movement in 2020 was not completely useless: it signalled that a social shift in salience was underway, at least to those with underlying sympathy.

The same thing applies to greenwashing. Though it’s less effective than when coming from a familiar or trusted messenger, it is likely actually helping a bit by telling people that others are taking action and that this issue matters socially. (And at the very least it’s a far cry from when this money was being spent on questioning the basic science of climate!)

So what?

Obviously I am not arguing that actual corporate ‘greenwashing’ or deflection, where it exists, is ok. At a policy level all organisations need to make and meet commitments which reduce their emissions, and they need to be held to account on that.

It’s just that when it comes to protecting a building a public consensus for climate action, it is not a big deal.

More than that, we can learn a bit from why this is so. As Yale have shown, social norm questions (“How often do you talk to your friends and family about climate?”, “to what extent do you think others would want you to care about climate?”, “to what extent do others in your life care about climate?”) are worth tracking alongside other measures. These are canaries in the coal mine for closing the gap between sympathy and action. We can also try building ‘dynamic norms’ into the messages we test.

Most importantly, worrying too much about greenwashing is a diversion of energy from our central task, especially as cost of living concerns rise up the agenda: keeping climate top of mind for the average voter.

We should see greenwashing as at worst a side-show to this. Either way it’s not worth getting too wound up about it. If anyone is being co-opted, it’s not us. And if that says anything, it’s that we can afford to be more generous about how we set the boundaries of ‘us’ and ‘them’ in the first place.