How to prevent a backlash on Electric Vehicles

This is not a culture war

Long-term readers of this newsletter will know that, in general, I’m a bit of a sceptic of the ‘greenlash’ hypothesis – the notion that the UK or Europe have suddenly become seized with anti-Net Zero sentiment.

As I wrote back in September, in most places polling evidence for this is pretty weak. Beyond isolated one-off scraps, a lot of the noise is media echo-chamber: at worst elite theatre, at best the sound of segments of the electorate that never liked the transition much to begin with agreeing with themselves a little more furiously. The radical right’s capture of Twitter - the biggest vibe emporium of them all – amps this up.

There are some areas, though, where that assessment is less true. Where vulnerabilities for green advocates are more real and generalised backlash a more tangible prospect. Almost always this seems to involve cars.

The rub here is simple. The UK’s shift to clean energy requires a move away from petrol and diesel and to electric vehicles (EVs).

But if you look at opinion trackers, the policy mechanism by which this will happen – the 2030 ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars – is one of the few green policies that genuinely has dipped slightly in public support in recent years (from net +9 to -9).

This arguably puts government and voters on a bit of a collision course. We have just seen Donald Trump exploit this in the US, spending millions of dollars on anti-EV ads in Michigan and making anti-EV policies some of his first as President.

So how can we best understand UK attitudes to electric vehicles right now, what pushes and pulls those views in different directions - and what does it tell us about the politics of the wider Net Zero agenda?

Persuasion UK and IPPR have today released an in-depth piece of research and message testing to explore this a bit more.

What we found is a pretty nuanced picture, one that can teach you quite a lot about fragmentation in the electorate and how voters think about issues more broadly.

The high levels of socialisation of EVs are a major ‘tailwind’ for EV advocates

To start with the good news for the pro EV side. While EV driving itself is still under 10%, all together about 50% of drivers now either own an electric car themselves or have at least one close friend or family member who does. There are some demographic differences, but it’s still pretty ecumenical.

This matters not just as a sign of their increasing uptake, but because it ‘social proofs’ the transition. It becomes harder to convincingly argue EVs are just the stuff of metro-elites.

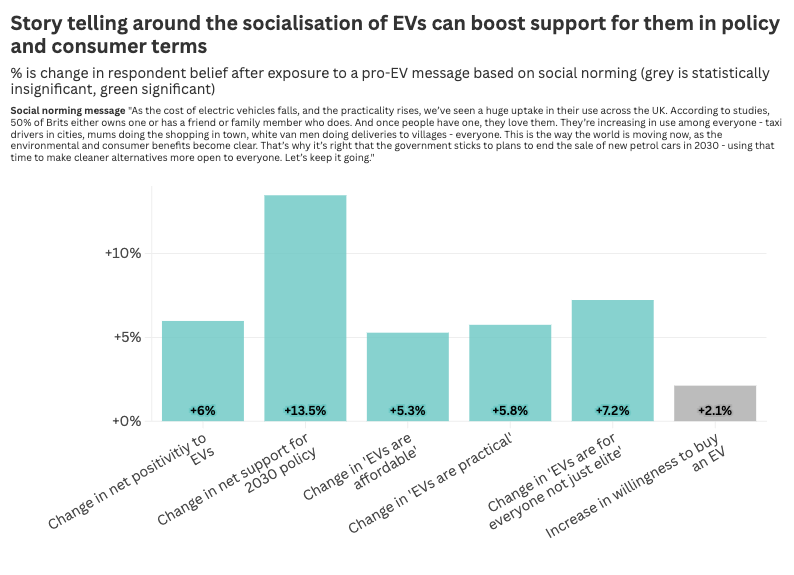

In fact, it turns out that, nudge based messages based on storytelling about socialisation are among the most effective are driving up support for the EV transition, as we see below.

There is baseline positivity towards EVs – but it’s soft and vulnerable to opposition messaging on cost and practicality

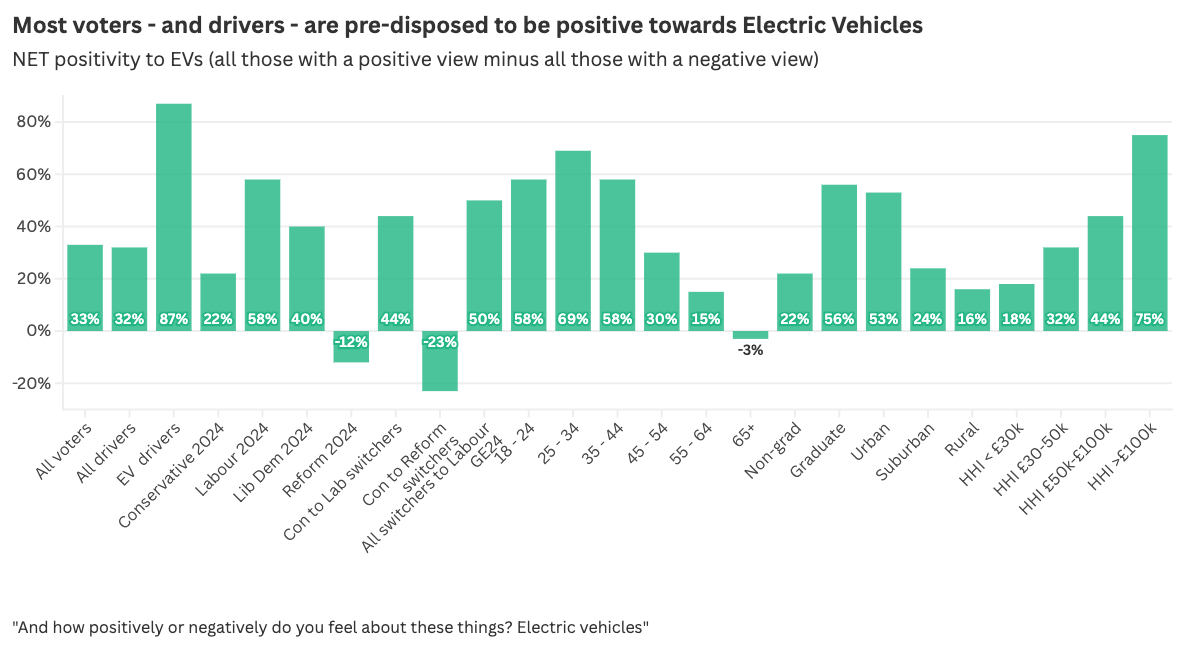

It’s partly the above, and a latent environmentalism in the electorate that means people’s overall disposition to EVs is favourable. This is especially true of the Labour coalition, including crucial Con-to-Lab switchers.

In fact we found the only segment of the electorate with consistently anti-EV views to be Con-to-Reform switchers. As is so often the case, they don’t represent ordinary voters.

We also find 60% of those in the market for a new car in the coming years would consider an EV.

However, its beneath the surface where you see a fair bit more ambivalence.

Generally, EVs are still not seen as especially affordable or practical. Throughout the research there is a particular anxiety about all things charging; sometimes the smallest hassles were the most frequently cited in focus groups (second-hand stories of charger-finder apps that aren’t inter-operable; worries people would get stuck at public charging points for ages with their kids in the back, etc). This is arguably unfair based on most people’s experience of actually owning an EV, but it is what it is.

Charging anxiety and cost anxiety feed into each other, such that – combined with an inherent British small-c conservativism- in our consumer conjoint an EV had to be half the price of a petrol car to be chosen as preferable.

This is unlikely to be the case even by 2030 or 2035.

The risk here is fairly obvious: of making the only first-hand car available to purchase one that is seen as less convenient, or affordable, than now.

It’s this which makes the EV agenda vulnerable to particular messaging focused on these practicalities, as we see below:

This is not a culture war!

At this point, it is worth making clear what opposition to the 2030 policy is not – and to provide some reassurance to green campaigners.

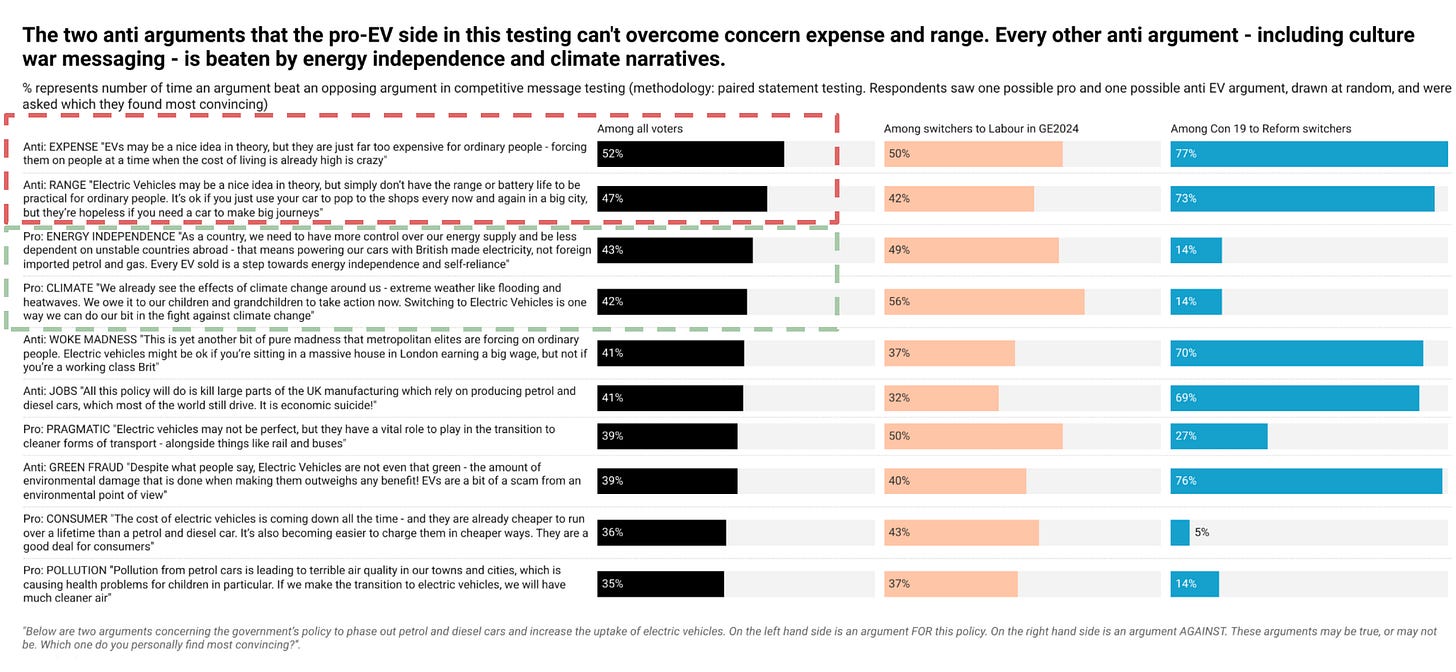

When you do paired statement testing - show people one random pro EV message against one random anti, and ask one most people find convincing (incl a don’t know option) – it is not the culture war message (‘this is all woke nonsence’) which floats to the top, especially among the Labour swing voters so crucial to the government.

Two big picture pro-EV arguments – climate and energy independence – exist to head that off (some thoughts on why these might work are in the next section). Moreover, high profile social conservative messengers were some of the worst performing for the anti EV side in our messenger testing, too. And ‘job destruction’ doesn’t really stick either.

Instead, it is entirely good faith concerns about charging and cost which are the ones pro-EV messages can’t overcome when pit head-to-head.

I emphasise the good faith bit for a reason. About a third of those who worry EVs are impractical or unaffordable are still overall positive to EVs.

This apparent paradox is easy to dismiss but it matters and is revealing.

We under-rate the extent to which voters think about issues with both civic and consumer ‘hats’ on, wrongly assuming they are solely transactional. Both matter to making sense of their views on many topics. With a civic hat on, EVs are good. The challenge is with a consumer hat, people are less sure. The brand of EVs is less Harrods, more Waitrose – aspirational but a bit up-market.

This is a challenge for the 2030 policy and explains why opinion on it is so divided.

The reverse challenge exists for EV opponents, incidentally. Many voters have EV anxieties but don’t want to be lumped in with wider anti-Net Zero rhetoric they still find a bit weird. This is precisely why anti-EV advocates best messages both start with ‘EVs are nice in theory, but…’ rather than rejecting the entire premise.

What is to be done? On policy and message

Two things are necessary, if Net Zero policymakers and campaigners want to avoid backlash in this area.

The first is throwing whatever it takes at good policy. That means a relentless focus on frictionlessness – especially on cost and charging. It is faff, not Farage that risks killing the EV transition. However unreasonable a demand it may seem to true green believers, people need be able to drive the same model of car as they do now, living the same kind of lifestyle they do now, just powered in a different way.

IPPR have today made some strong recommendations to government in this vein off the back of our research. You can read those here. One of them, for instance, involves cutting VAT on public charging so it’s equal with home charging – so people without driveways, likelier to be less affluent drivers, are not punished for it.

Beyond that, communications still matters - pro EV messages can work if they are heard. As we saw earlier, stories of growing uptake of EVs seem to ease consumer anxiety more than battering people over the head with stats about falling costs. They should be used by EV advocates.

But what I call ‘big why’ messages still matter and work too, especially on the 2030 policy. Climate and energy independence yet again jump out from the message testing. This may be counter-intuitive but it’s back to that ‘civic hat’ point – it reminds people why this whole thing is happening to begin with, causes people support. The risk otherwise is this all appears like entirely random government policymaking, falling from the sky.

Such civic messages are not enough on its own, but they shouldn’t be abandoned entirely. Good comms and advertising should still find space for them.

In general, the fact people can be equally swayed by anti and pro messages shows you how soft opinion is – but also how much it’s still all to play for in this space.

(Meanwhile, I should note this was another set of message testing where the pro-jobs messages work better with elites than voters.)

So what?

All of which seems do’able enough. But what concerns me a bit as someone supportive of Net Zero is, aside from a core of those working on it, this issue – the consumer side of EVs - still flies under the radar a bit in terms of government and advocacy attention.

I may be wrong, but it sometimes seems to me there is more head space given to less important or salvagable things. Corralling trade unions or car manufacturers; abating the infernal din of Daily Telegraph headlines; trying to assuage people who think Greta Thunberg causes chemtrails, whatever. These things may create noise, but they matter much less.

It is right here, this place – in the boring elements of the less glamorous parts of Net Zero - that we find the molten core of the entire project, both politically and in policy terms. The middle ground consumer concerns of middle ground voters: positive, wanting to the right thing, but feeling more squeezed than ever.

Simply put, they need help and the right levels of reassurance. Right now, they are not paying too much attention to the EV switch. There is still time to get it right before they do, but the clock is ticking louder than before.

If you found this in any way useful or interesting please do share it! Tweet thread you can RT is here, the equivalent on BlueSky is here.

A summary of the research, plus the full-length research in all its depth, can be found on the Persuasion UK website. IPPR’s policy calls are on their website.

Thanks to all those who worked on this project, and to the YouGov political team for helping collect the data.

How much of the dip in support do you think is simply due to 2030 getting nearer? I suspect there is a natural cycle where a date far in the future for any restriction/ban or similar usually sees its support drop as the date becomes nearer and so the potential loss or inconvenience to people feels more immediate?

There is an implication from the graphs that older people in lower socio-economic groups are more hostile to EVs than younger people in higher socio-economic groups. I suspect that there's also lower enthusiasm for EVs the further away from large conurbations the person asked lives.