Tracking public attitudes to borrowing

It’s complicated, but it’s also not 2014

You should always beware people brandishing simple truths, except when they do so in this newsletter. One such unavoidable fact, in my view, is this: Britain is a low-investment country and this explains more or less everything about the whiff of managed decline lingering around our economy and public life in 2024.

If you won’t hear it from me, more august individuals and institutions are available.

Though afflicting both public and private sector, on the public side this tends to be held in place by successive government’s fiscal rules. These have traditionally taken a pretty one-eyed view of the government balance sheet while treating borrowing for day-to-day spending and long-term investment in the same way.

Despite playing a role in keeping growth low and debt high, these norms persist for multiple, complex reasons. Much of it is just Treasury orthodoxy.

But in Westminster, a big part of what closes down political space for challenge is a basic assumption about public opinion: voters will reward any party that prioritises getting debt down, punishing anyone seen as even remotely pro-borrowing, whatever the purpose and whatever the long term logic.

It’s perhaps uncertainty over how much this law of gravity still holds that partly explains the to-and-fro over Labour’s £28 billion Green Prosperity Plan, for instance - on display again this morning.

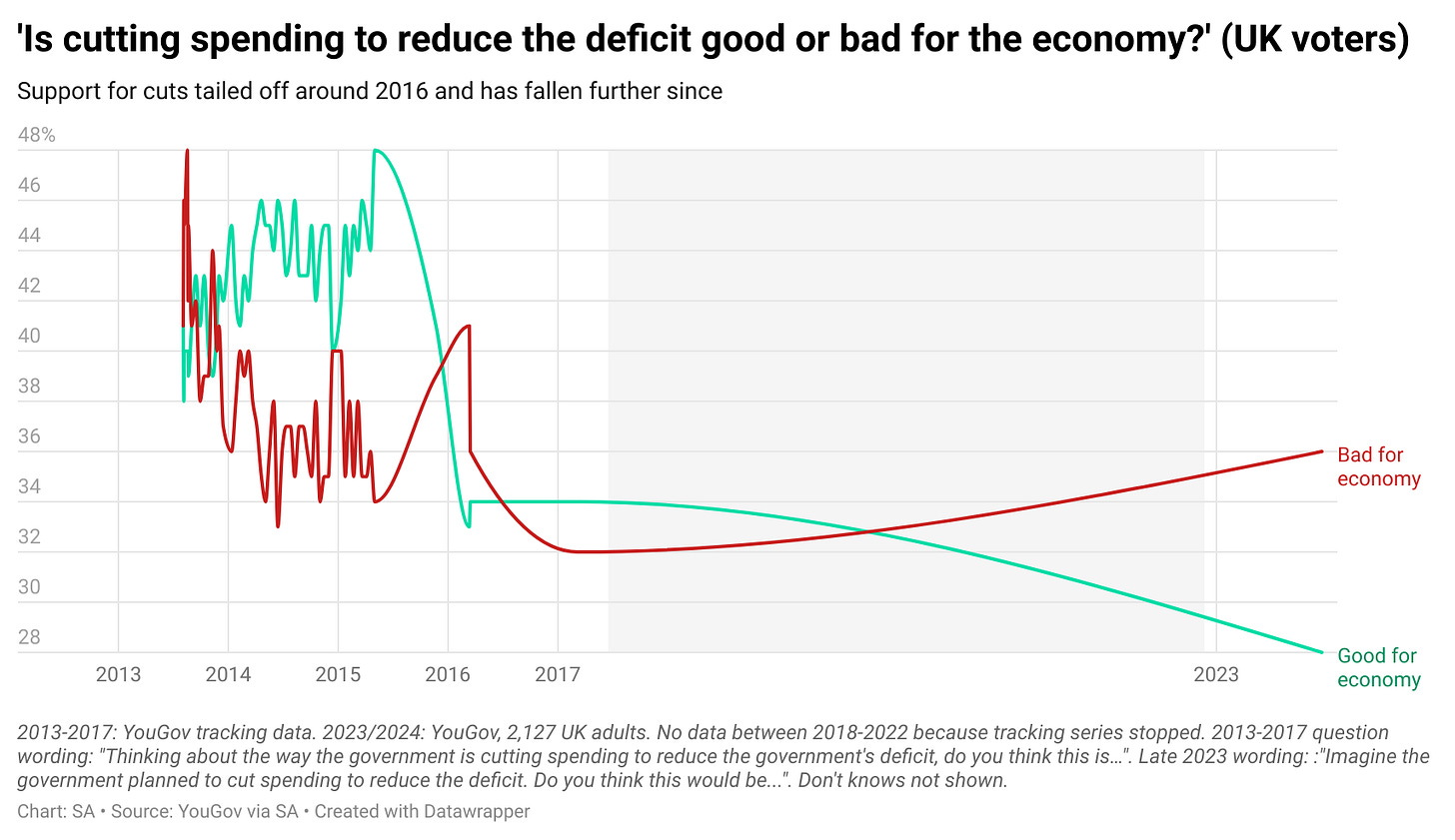

The case for caution certainly has historical merit. It's an inconvenient fact for the left that the Cameron-Osborne austerity years were not done to voters; they took place in the backdrop of high levels of public alarm at government debt/deficits and clear support for public spending cuts. This was not purely the creation of the CCHQ comms machine.

So how much of that is still true? To get at this, I worked with the excellent Economic Change Unit (ECU), YouGov and others to dig out some old questions on this area and run them again, alongside some new ones, to see how things have moved.

We can see three broad things:

1. Most voters still do not love the idea of deficit spending or borrowing.

It’s worth starting with what hasn’t changed. Voters have not suddenly become fluent in modern monetary theory. Focus groups will almost always greet any grand idea with ‘but where’s the money coming from?’ and some participants will instinctively flinch if the answer involves debt (“we’re already in a lot of debt”). Most have not abandoned the household budget metaphor, infamous in progressive circles.

We can see this if we re-run the below question, first seen in the 2015 Cruddas review of Labour’s defeat that year (no, people don’t tend to distinguish debt and deficit).

The wording itself is pretty push-polly - but the fact it hasn’t moved much tells a story. In isolation, it remains possible to generate polling results like this fairly easily.

Here is the thing, though. In order to get under the skin of public attitudes, you need to look not just at isolated attitudes but the importance they attach to them and how people wrestle with trade-offs, when presented. It’s here where things have moved most, I think:

2. The salience of debt and borrowing as a problem is significantly lower than a decade ago.

Ten years ago, worries about government indebtedness dominated people’s entire notion of ‘the economy’ - how they felt it was performing and who they truly trusted on it. As Ben Walker and others have noted, that is very clearly not the case today.

When you now ask people all of the things they consider when thinking about the economic health of the nation, government debt is at the bottom of the list – in 2013 it was third.

When you press them to choose their top 3, just 16% of the population choose government borrowing. It has become swamped by worries over inflation, interest rates and other concerns.

This is important on its own terms, but especially in how it weighs on voters minds when they start to consider different trade-offs when presented.

So for instance, if we take one thing voters don’t instinctively like (borrowing) and play it off against something they generally do (investment), what happens? Investment now wins in basically every area apart from welfare, something which people tend to see as less of an investment in the future.

Part of this is debt and deficits falling off the news agenda, but some of it is also about the legacy of an austerity program which eventually exhausted public support.

3. This creates an opening for progressive parties, if they are careful…

It is these dynamics which ultimately explain why borrow-to-invest arguments now quite clearly beat debt reduction narratives, as we can see in the final two graphs below.

For this I ran a paired statement. Since messengers matter and this is an area of historic brand weakness for Labour in particular, I asked a separate sample the same question but with party labels attached .

The result is fairly convincing – a 30%+ margin for borrow to invest over the opposite argument.

The gap narrows when you introduce party politics, as you’d expect - some of that is base voters sorting their views according to their ‘team’. But it’s still comfortable, with a hypothetical Labour argument carrying a clear plurality of voters and 17% of 2019 Conservative voters, more than the 12% they have in current polling.

At least in principle then, an election which played out on these grounds is one where Labour start in a reasonably strong place, especially given their generally improved brand.

Keir Starmer has repeatedly shown flashes of self-confidence to this effect (this morning being the latest, but there are others). It’s just not entirely clear this is held across the entire party right now.

So what?

More generally, what to take from this for progressive campaigners? Well, it is not a free lunch. Average voters will always be sceptical of spraying cash around – it’s basic hygiene and credibility to avoid this perception. If you can hypothecate an idea (tax X to fund Y), that is still best. Showing responsibility still matters.

But there clearly is an opening around borrowing to invest, separating out different kinds of spending, if the case is made carefully. It needs to be for very specific purposes, something voters can see has a long term benefit. And come from messengers that are at least not actively distrusted.

Tony Blair famously observed a distinction between a three second conversation with a voter and a thirty second one, or indeed a three minute one. In his case, he used this to cast doubt on top-line polling support for rail nationalisation: voters like it in principle, less so when they stop to consider the counter argument.

The same applies here. Voters can still flinch at borrowing but - these days at least - move fairly speedily from that position when trade-offs and counter arguments are surfaced.

Getting that 30 seconds is the hard bit of course. But it is easier in election years.

And even if 3 second household budget argument remains, people at least get that if you want to improve your house you might need to take a loan, and that this is different than doing so to buy a new TV or do a Waitrose shop. Especially now the roof is crumbling.

Finally…

All this is also a useful case study in how to think about polling and prod at public attitudes generally, I think.

In this area as in most, it’s possible to see contradictory poll results - voters like one thing but also its direct opposite - and become exasperated with the discipline of polling itself.

But while one-sided surveys don’t help, this just reflects the natural ambivalence of voters themselves.

Less partisan swing voters especially do not have particularly fixed or ideological opinions (something that accounts for their inherent reasonableness, in my view). On any given issue they regularly hold in their head a melange of competing thoughts, instincts, interests. Focus groups regularly swirl with contradictory narratives.

The trick is trying to draw out how they trade these things off, to the extent they do, and what is most salient at any moment in time. It’s this which ultimately shapes the parameters of the possible and, with it, election results.

In this case, it is possible to see those parameters shifting. If politics can catch up, the next decade can still be better than the last.

* If anybody would like the tables for any of the baselines or new polling appearing here, please DM me on Twitter.