Understanding voter attitudes to the 2025 Budget

Stepping into the land of least worst options.

In about a month’s time, the Labour government will make its second major attempt to patch up the British state and economy. In truth this is a fate you shouldn’t wish on your worst enemy, comprising as it does a fairly hellish set of riddles and booby traps on cost of living, public services and economic growth – all trading-off against each other in ways that are not huge fun.

This year’s jape is that Chancellor needs to find roughly £30-40 billion just to stand still on her day-to-day spending rules, nevermind fix much.

With further changes to fiscal rules or large-scale spending cuts likely off limits, tax is the major available lever. Except, for reasons of varying intelligibility, Labour’s manifesto pledged not to touch any of the ones that reliably raise revenue (see what I mean about fun?).

The basic choice then is this: raise a lot of small and narrowly targeted taxes, fill in the hole and move on - or go bigger and bolder, breaching the manifesto as you go.

How should policymakers and observers think about voter attitudes in this context? I have a new report out with Persuasion UK today that tries to help, as featured on the New Statesman podcast. To my knowledge it’s the most in-depth look yet at this year’s Budget and has wide-ranging polling, experimentation and message testing.

The full thing is here – I can’t cover everything here, but below are my main take aways.

Fairly obviously, this a really tough environment to ask ordinary people to pay more tax – most people’s strong preference is that the wealthiest pay more.

To a striking extent, the willingness of a voter to pay more tax can be positively predicted by just three variables: their personal income, their level of support for the government and then efficacy: to what extent do they think greater investment is needed in public services and trust the state to spend money raised effectively?

The bad news for Labour is all of these indicators currently point downward for most voters.

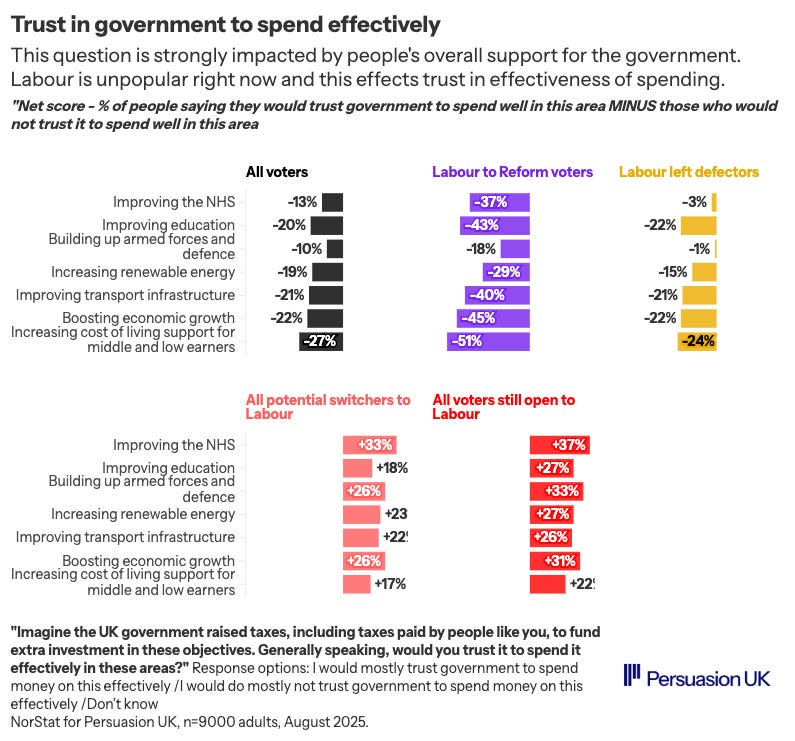

Pretty much every major group currently feels they put more into the state than they get out, while there’s basically no area voters overall trust the government to spend money well in. Building up the military is the only one where a plurality of voters accept investment is needed to drive improvement rather than just efficiency.

This is, of course, partly a function of low trust in a government that arrived into office with a fairly shallow pool of voters loyal to it. Things are a bit brighter within that coalition, but not hugely.

All in all then, not the best starting point. In this environment, we find an ‘anyone but me’ dynamic. Voters very strong first preference is for those at the top to pay more – roughly constituted as anyone with wealth over £1 million or an income over £100,000. Big banks, social media and gambling companies, oil and gas firms and so on; all easy targets in this context. In fact only a handful of groups are off-limits: pensioners with under £300k, small business, farmers and petrol car drivers.

Westminster likes to be dismissive of such findings but we found attitudes to be pretty robust. For instance, take increasing CGT or landlord taxation; even when voters were exposed to the most sympathetic case study imaginable (an ‘edge case’ of someone more normal who’d be hit by the tax), support remained net positive.

Elsewhere, the ‘millionaire exodus’ argument fell-flat with voters by 3:1.

There may be good public policy reasons not to raise these kind of taxes, but there are no good public attitude ones.

If the government can deliver on the priorities of its voter coalition just through these type of levies, then, or even tweaking fiscal rules, it should do so. The bigger challenge is: what if it can’t? What if the OBR or policy reality impinge, and the choice is sharper than that?

If the choice really is failing or breaching the manifesto, breaching the manifesto is the least worst option.

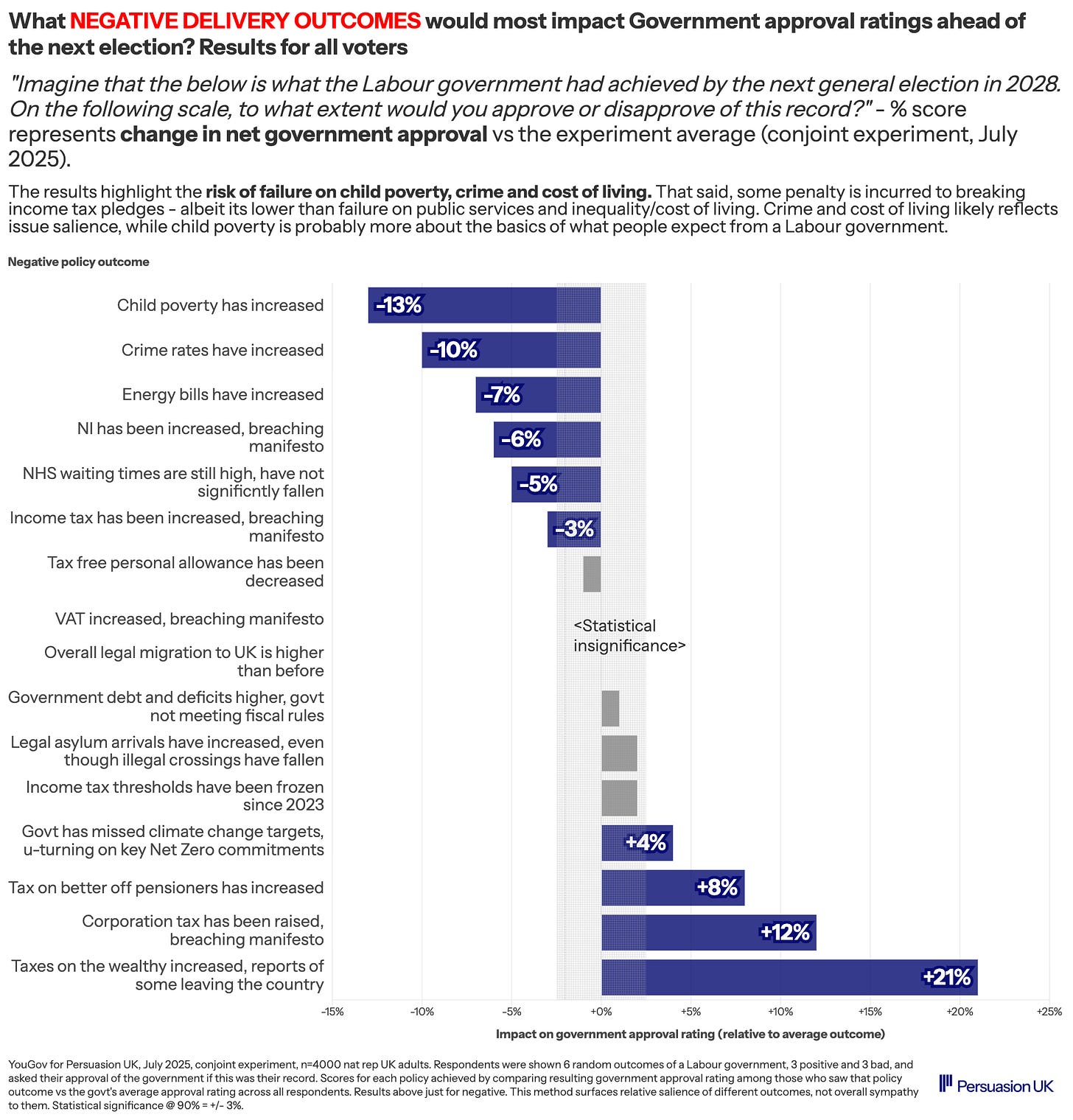

One of the most revealing parts of the research was when we started to force trade-offs on voters that government itself may face. About 4,000 voters were invited into an experiment where they were shown a charge sheet – three government achievements, three government failures – and asked to imagine it was the record Labour were standing for re-election on in 2028.

The success and failures were pulled at random from a long list. Each respondent is asked to what extent they’d approve of the government if it stood on that record. We throw in failure to keep to key tax pledges alongside other public policy shortcomings.

In the analysis phase, we see which outcomes push up and down most on average government approval. You obviously cannot model these sorts of things perfectly in such an experiment, but you can at least better surface the balance of punishment and reward facing the government.

As you can see below, the results offer a fairly clear picture. There is some penalty for breaking manifesto pledges on income tax or NI. But it is less than the penalty incurred for manifest failure on the public realm (NHS and crime), cost of living (energy bills) or large scale increases in child poverty.

Conjoint experiment results with all voters:

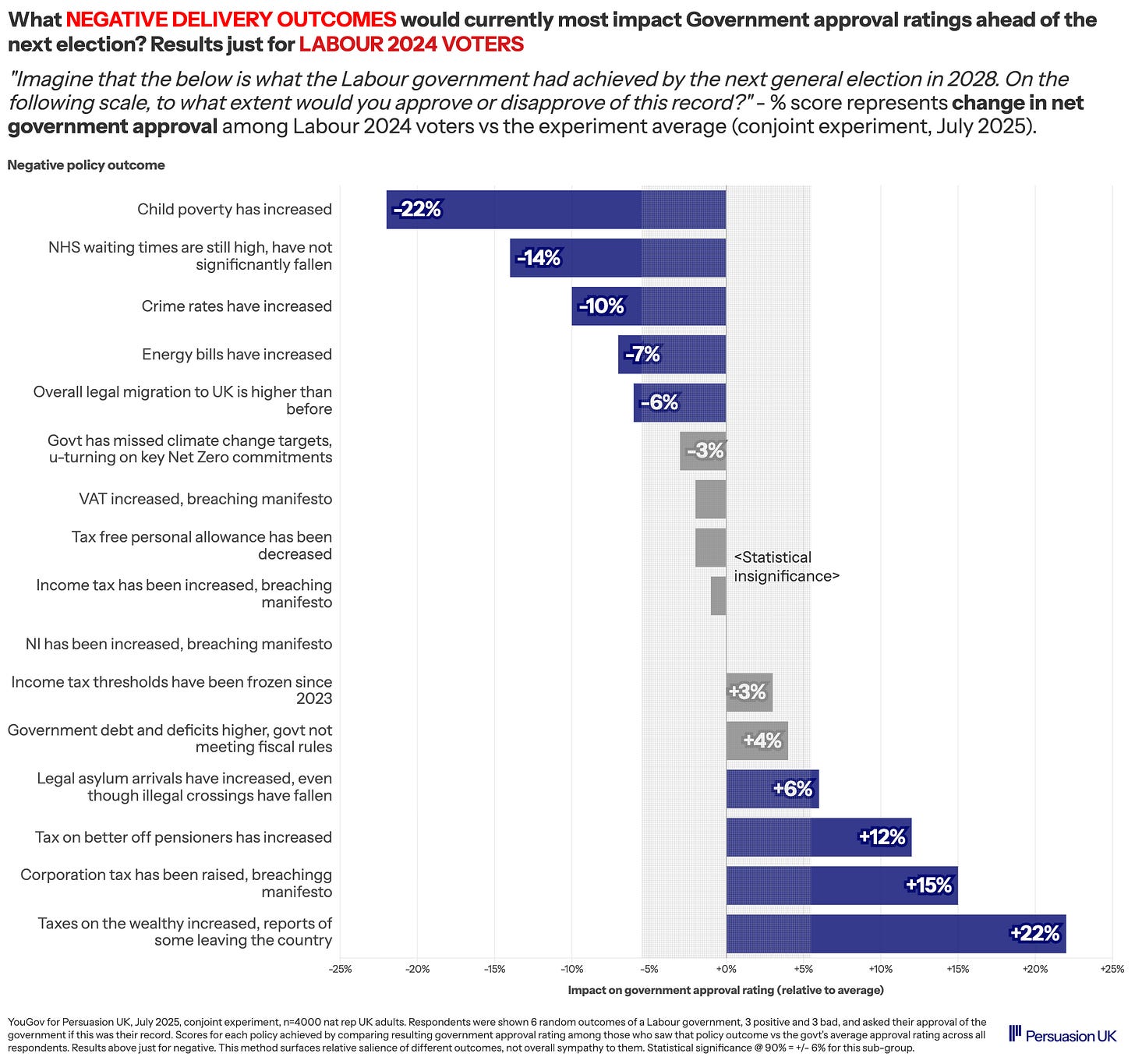

This dynamic is particularly intense with the average Labour 2024 voter, where punishment for tax rises was minimal but punishment for failure elsewhere amplified:

Conjoint experiment results just for Labour 2024 voters:

Meanwhile, on the ‘reward’ side of the ledger, in the full report, we find the salience of public service outcomes, especially the NHS, as well as things like climate to Labour voters uniquely.

How to make sense of all this?

In short, that if the choice is genuinely between failing on key public policy areas or breaching the manifesto, breaching the manifesto is the least worst option for the government.

Some of this is about expectations, I think, particularly the child poverty result, which surprised me. Despite all the brand re-positioning Labour did, at some level voters know Labour governments may put up taxes. What they don’t expect is for them to fail on public services, inequality or cost of living, issues more intimately connected to the brand - so the punishment beating for doing that is larger. A sort of ‘well what’s the point of you then’ vibe.

Indeed, in my view it is precisely because voters started caring more about Britain’s crumbling public realm than other considerations that they elected Labour to begin with. Not being cavalier with people’s money or the economy generally was important hygiene - or table stakes - after Corbyn, but it’s not what won it for Starmer.

3. The best way of selling a manifesto breach is probably to go big, be positive and focus on cost of living – but Labour might need to speak to a broader coalition of voters.

This still leaves the question of how one might communicate such a massive change, and it would be extremely tough; this is already a very unpopular government and people are feeling very squeezed and distrustful.

Substance matters here, though. Probably the worst place electorally is to raise enough tax to piss people off but not enough to actually improve anything tangible in their lives.

My personal view is that if government is forced to do this, it should do it properly. Raise enough to give something back to voters in short-term cost of living schemes (large energy bill discounts - send a cheque in the post! - plus childcare expansion etc), put some into public services that need it and are visible locally - and the rest into headroom for the Parliament.

At that point the government has a more positive message rather than a crabby or defensive one, and it doesn’t have to keep coming back to do unpleasant things.

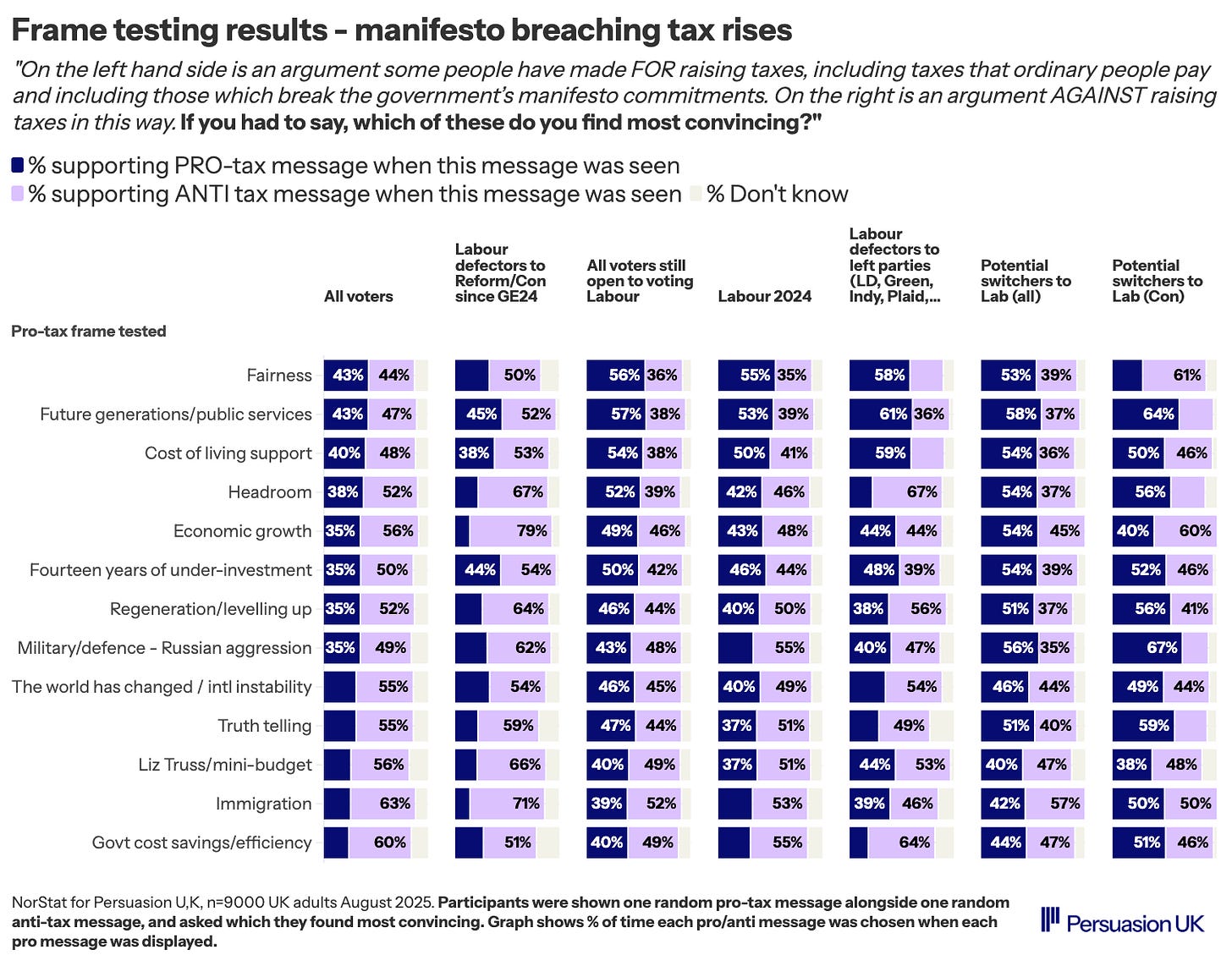

To some extent, the competitive message testing we did in the report bears this out, as below (sorry it’s a busy graph but there was a lot to test!). In terms of the best performing ‘pro’ tax rise measures, it’s important that people hear the richest are still being asked to pay more (‘Fairness’ message). But beyond that, it was cost of living and re-building public services messages that perform best.

Competitive message testing results - how often a pro-tax message beat the anti tax message, among what groups:

It is worth noting it is still a slog, though, and opponents have many effective messages available to them – especially linking extra tax to government waste or asylum hotels.

As you’ll note, even the best performing messages don’t carry a majority of voters clearly - it’s why you don’t do it if you don’t have to.

That said, the government arguably only needs to win its own coalition and that is a slightly easier task. As you look across the graph, you see it has more success with its own target - or potential target - voters than the population at large, even if it might require a slightly different constellation to its 2024 coalition.

All in all, a very difficult task for government, but not an altogether impossible one. At least if it plays the long game.

So what?

There’s a scene in Oliver Stone’s Nixon when Henry Kissinger – Watergate bringing down the White House around him - laments to his stricken boss: “to be undone by a third-rate burglary is a fate of biblical proportions”.

For Labour MPs and activists, waiting 14 years for their party to return to power, to be undone by the strategic genius of Jeremy Hunt is not much better.

It was after all in responding to traps laid by the former Conservative Chancellor that the party tightened the straps on its fiscal straight-jacket. The scar tissue of election defeats and cost of living pressures made that explicable at least – but it was always extremely risky given the state of the country and the shape of their mandate to fix it.

Whether Starmer and Reeves can indeed extricate themselves from that predicament in one piece remains a fundamental question for the coming year – one which will likely not only shape how we are governed, but by whom.