Uxbridge is not Britain

Quantifying Tory brand risk from climate delay – some new research, plus thoughts on what happens next

Perhaps more than is appreciated, British political parties are still mostly creatures of instinct. For all the rise of data and focus groups and other supposed forms of organised cleverness, a lot of their learning process is still basically Pavlovian - conditioned by when they last got a painful whack on the nose or received a satisfying reward.

This is why the Uxbridge by-election mattered. Whatever the logical flaws, a powerful narrative settled over SW1 that there were votes to be had in opposing green policy and, somehow by extension, Net Zero policy generally.

A flagship Sunak speech followed, taking as its headline measure a delay to the 2030 target for phasing out the sale of new petrol and diesel cars.

This not only upended years of political consensus on climate, it marked an entirely new phase of the Sunak premiership.

A month on, though, it does not seem to have done that much for them in the polls or, indeed, subsequent by-elections.

Why? After all, the lead policy in the speech polls relatively well (even if very dependent on question wording).

Most of the time when public opinion is unmoved it’s just because most people don’t pay attention. This is Lord Frost’s argument: what’s needed is repetition!

I think, though, that the problem for Net Zero sceptics goes deeper. Let’s say we could, Clockwork Orange style, force voters to learn about Sunak’s September intervention. What would happen?

What happens when people see ‘climate delay’ policies and platforms?

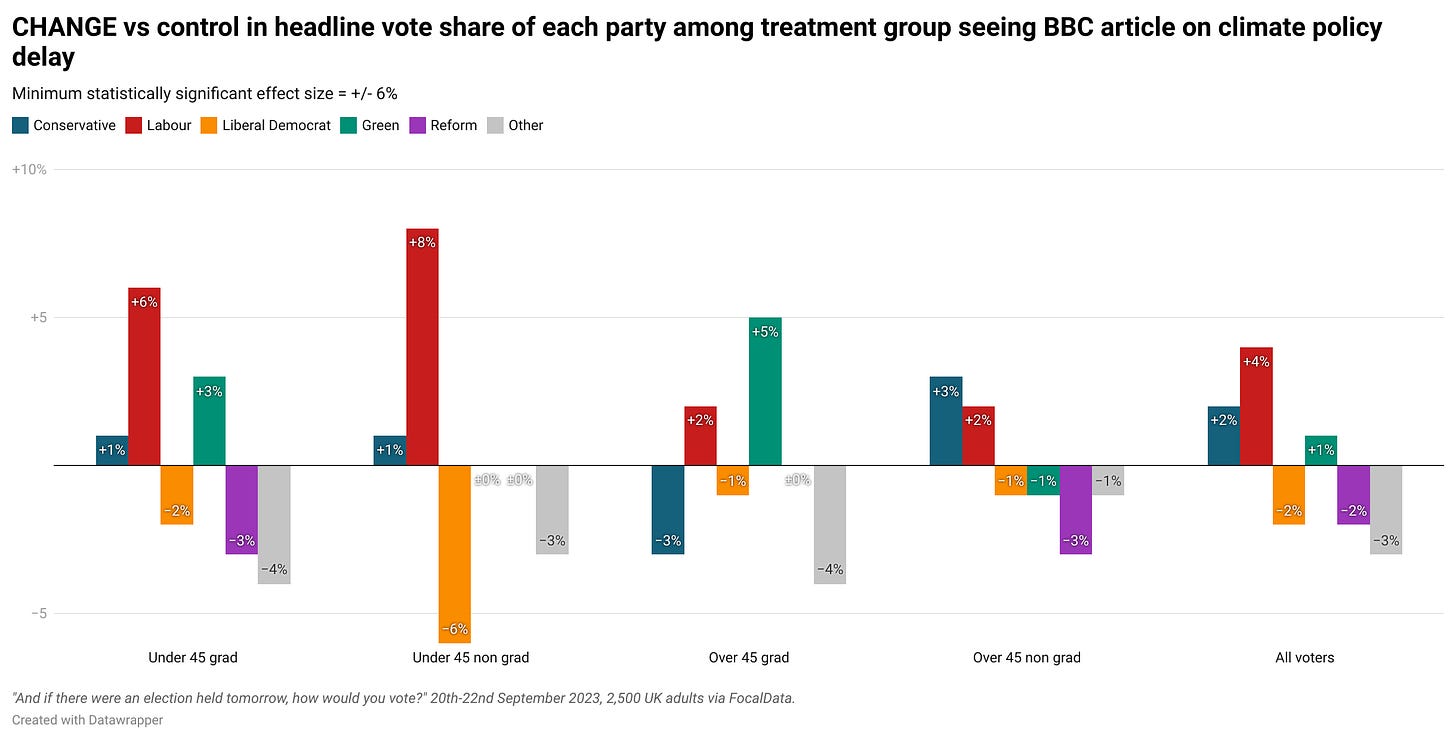

To get at this, I set up a small RCT (Randomised Control Trial) experiment with FocalData on the day of Sunak’s speech. A treatment group of voters saw a shortened version of this neutral BBC article regarding Sunak’s announcement, while a control group saw nothing. Both groups took the same survey at the end. Any statistically significant difference (minimum 6% +/-) can be attributed to reading the article.

So what happened for the Conservatives in the treatment group compared to control? In short, not much good.

Among their target voters – Conservative 2019 voters; non-grads aged over 45 – there was no statistically significant change in the Conservative’s vote. It did not bring back ‘don’t knows’ nor Con-to-Lab switchers. Neither was there any greater positivity toward the party or Sunak himself. This is despite support for delay to the petrol/diesel phase out date being higher in these demographics than average.

The only meaningful movement is among under 45s and graduates. Here favourability towards both the Tories and Sunak plummets further.

In this experiment at least, all that does is help Labour consolidate its base, squeezing wavering Labour-Lib Dem vote. Given the massive role tactical voting has had in every single Conservative by-elections defeat this Parliament, this really should make the Conservative’s think long and hard.

All told, these are not exactly the hallmarks of a potent wedge issue.

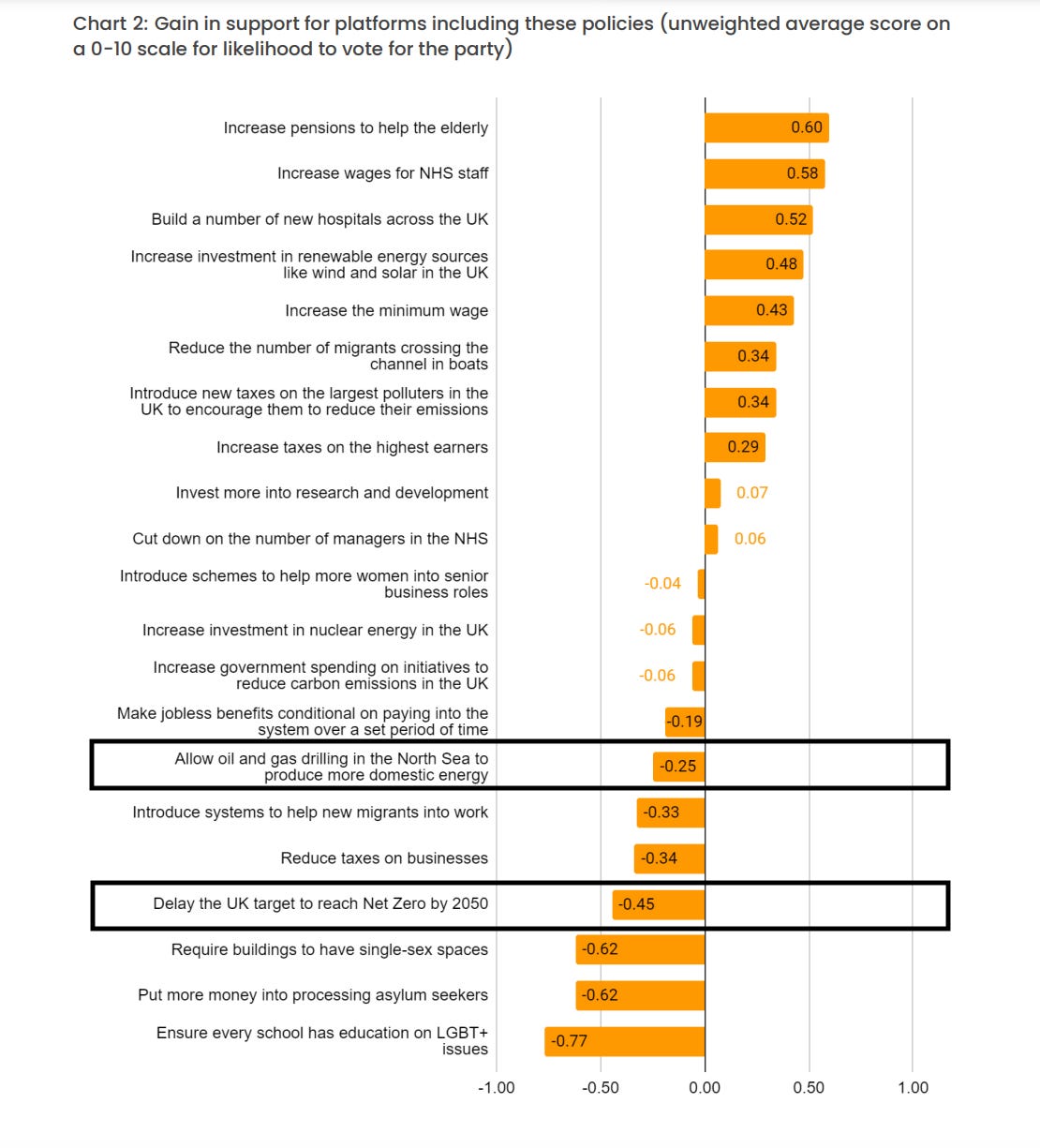

Separately, this is backed up by a great new paper today Public First. Here, each survey respondent is asked which party they’d vote for, Party A or B – with both parties represented by a platform of 3 policies randomly chosen from a list of 21 (across a range of policy areas). In the analysis phase we can see which ideas have the biggest impact to which party voters chose – revealing their policy priorities.

The results show a number of striking things. Of most interest here is quite how poorly ‘Net Zero delay’ or expanded oil and gas drilling did – being among a handful of policies which actively repelled respondents. The blockbusting popularity of renewables also leaps out.

The report goes into more depth on this (on p.27), makings clear the dynamics behind these results. Opponents of Net Zero delay are far more likely to see this as a vote moving issue than are supporters, concentrated among Remainers (including Conservative Remainers) and graduates.

Worryingly for the Conservatives, anti climate measures are also starting to become associated with the Tory brand (p.23).

This, then, is the basic rub of policies perceived as anti Net Zero. It further alienates demographics which, long term, the Conservatives need to re-build with (especially in Blue Wall seats) while gaining them basically nothing with their 2019 coalition.

Why? Because, by default at least, even Conservative 2019 swing voters do not instinctively trade climate or environmental action off against cost of living. Most care about both and don’t see them in inherent tension.

Yes, there are some voters who when forced into a corner by a pollster will say they’d quite like to go a bit slower on this or that slightly inconvenient sounding Net Zero policy.

But, most of the time anyway, they don’t care all that much – because the trade-off is not real. It’s all a bit arid and abstract, somewhere down the line.

Whereas, as we’ve seen, those more committed to environmental action – a really not negligible chunk of the electorate especially in the Blue Wall – really do care; for many it’s a part of their political identity. Basic support/oppose polling can miss these asymmetries.

It's here where Uxbridge was exceptional. The incoming cost of ULEZ expansion was both proximate and urgent, making the trade-off between ‘green stuff’ and cost of living much more real and immediate and the anger more intense as a result. The same goes for Germany’s controversial 2024 heat pump law. A trade-off was forced and understandably, cost of living concerns won out.

For now at least, that context is not present in the wider UK Net Zero agenda, much of which is happening in the relatively distant future - and none of which directly takes cash out of the pockets of ordinary people like ULEZ.

Absent some credible threat, the risk of being seen as anti-environment has a better chance of prevailing over the reward of being seen as pro cost of living.

Briefly: media matters

The other thing that will influence that dynamic is media framing. Sunak’s team may object that his speech was not explicitly anti-Net Zero, and it did tread a careful line in this regard. But there is no doubt that - outside of a handful of ultra loyal newspapers - this was how the media framed it (the BBC story I based the RCT on being an exemplar).

I’m not sure No 10 can complain about this, though. Firstly, it seemed happy for the media to report this way, reflecting a strategic ambiguity about ‘red meat’ which goes to the heart of the Sunak premiership. Even if they weren’t, though, the media will probably always cover it like this. A large amount of the lobby is just very into the idea of a climate culture war! (Weirdly so, in fact. I suppose it’s a sexy angle on an otherwise dry policy area).

It of course remains theoretically possible for the Tories to come back and have another go at climate delay, doing a better job of navigating a rocky path. But it’s nowhere near as easy as they think. And right now, to me at least, electorally it looks a lot more hassle than it’s worth.

Ok, so what?

All of which should not be a cause for complacency among Net Zero advocates.

The ground may not be fertile for generalised backlash right now but that can change. About the only meaningful structural shift in wider public attitudes in the last few years is a vastly increased sensitivity to cost and inconvenience.

As I’ve argued, this is not unique to climate - but it’s not irrelevant either. Depending on the result of the next election, within 3-4 years the phasing in of electric vehicles and heat pumps will become far more real, the phasing out of petrol cars and gas boilers more concrete.

Broadly speaking, right now the up-front cost of the green alternative still remain higher than what it’s replacing - to say nothing of things like charging infrastructure for EVs. If that is still true when those policies kick in, the ensuing fall-out will make Uxbridge look like a tea party - for whichever party is in office. It won’t matter how good the comms or engagement is.

This is where far greater focus is needed. Fretting about cultural polarisation or whatever your uncle is sharing about 15 minute cities on Facebook is a bit of distraction from the central challenge: making the transition to cleaner energy as inexpensive and convenient for the average voter as humanly possible, by whatever means necessary, while continuing to communicate why it’s necessary.

In this effort, who pays? What is the balance of costs between the consumer, business and government? Do we go the Biden route of subsidy, or something else?

A lot could come down to how a possible Labour government responds (I hope to be able to do a post on this soon).

But, whoever is in power, it is still this question which will define how well Britain’s climate consensus holds up in the next decade. We have some time to get it right; but it’s important we do.