What happens when people see direct action protests on climate?

It’s complicated and it depends (sorry)

A few months ago, a friend who works for the BBC asked me if I wanted to go on The Ros Atkins show and talk about the recent Just Stop Oil (JSO) protests. Do these sorts of actions work? What effect do they have on public opinion?

Gore Vidal’s famous advice ringing in my ears, I wanted to say yes instantly. Ros Atkins is great; being on the tele is fun. My Mum might finally understand my job.

The trouble came when I started to think about what I’d say. I can bluff a bit but I was nagged by the sense that I really don’t know what I think on this. My instinct is that the effects aren’t great, but there’s some good arguments on the other side. And not that much decent UK research.

I have tried to address that with a new experiment. The idea being to test what effect these actions have on ordinary voters in the UK when they are exposed to them.

I’ve attempted this carefully and in genuine good faith. I have no wish to piss off anybody doing anything on the climate crisis, or to be an accessory to unjustified attacks on them. Doing something usually beats nothing, and we have very little time. But it’s also true that JSO and others can sometimes be vague about stacking up their theory of change or answering questions on it. Comparing yourself to the Suffragettes and dropping the mic doesn’t feel entirely sufficient.

Briefly: a word on methodology

For this Randomised Control Trial (RCT) video testing was used. RCTs work by taking a large group of people (in this case 3,000) and splitting them into demographically identical sub-groups (‘message groups’) and a control group. Each message group sees just one content package, then all of the groups – including control – take a polling survey on their attitudes to climate action.

Any statistically significant difference (in this case >4.4%) in the ‘outcome’ attitudes of a message group vs control can reasonably be attributed to the content they’ve seen. No experiment like this is ever perfect, all involve normative editorial decisions, but they’re usually better than the alternatives.

Since direct action protests often provoke polarising media discourse, to better mimic this, each message group saw a real-life news or content ‘package’ in the same structure: the protest that happened, someone speaking in favour of it, someone speaking against it. Where the video was a little too pro, I included an image of an anti-message to balance it out.

The five content packages covered:

1. JSO’s Van Gogh soup throwing protest plus this anti-message

2. JSO’s paint spraying of government buildings and News Corp, plus this anti-message

3. Insulate Britain’s (IB) road blocking protest

4. Extinction Rebellion (XR) and JSO’s anti-oil terminal road blockages plus anti message

5. XR’s 2019 direct action protests in London (first minute and a bit)

Each video was scored on its ability to meaningfully move people towards more pro-climate views across 9 key metrics (support for Net Zero policy, willingness to participate in civic action for climate, opposing anti-NZ sentiment, etc).

For final scoring, a protest gained a point when it positively moved the sample at large, or one of four sub-groups: under-40s, over-40s, graduates and non-graduates. It lost a point when it created a significant ‘backlash effect’ among these groups, i.e it turned more of them against climate action.

In general it’s a good idea to not get too hung up on individual metrics, but to look across the piece and see which video performs most consistently.

The research was done via Opinium UK in late November 2022.

Results

To stop this post becoming a flood of graphs, I’ve put the full results are in a deck here. But I’ll summarise them below.

Firstly, it’s worth noting that all the protests are viewed negatively among treatment group respondents when they are asked to rate them. However, direct action advocates reasonably argue that some things which are not prima facie popular can be effective, not least at commanding attention. The unique joy of RCTs is they allows us to observe this. What good was extracted in return? Attention to what end?

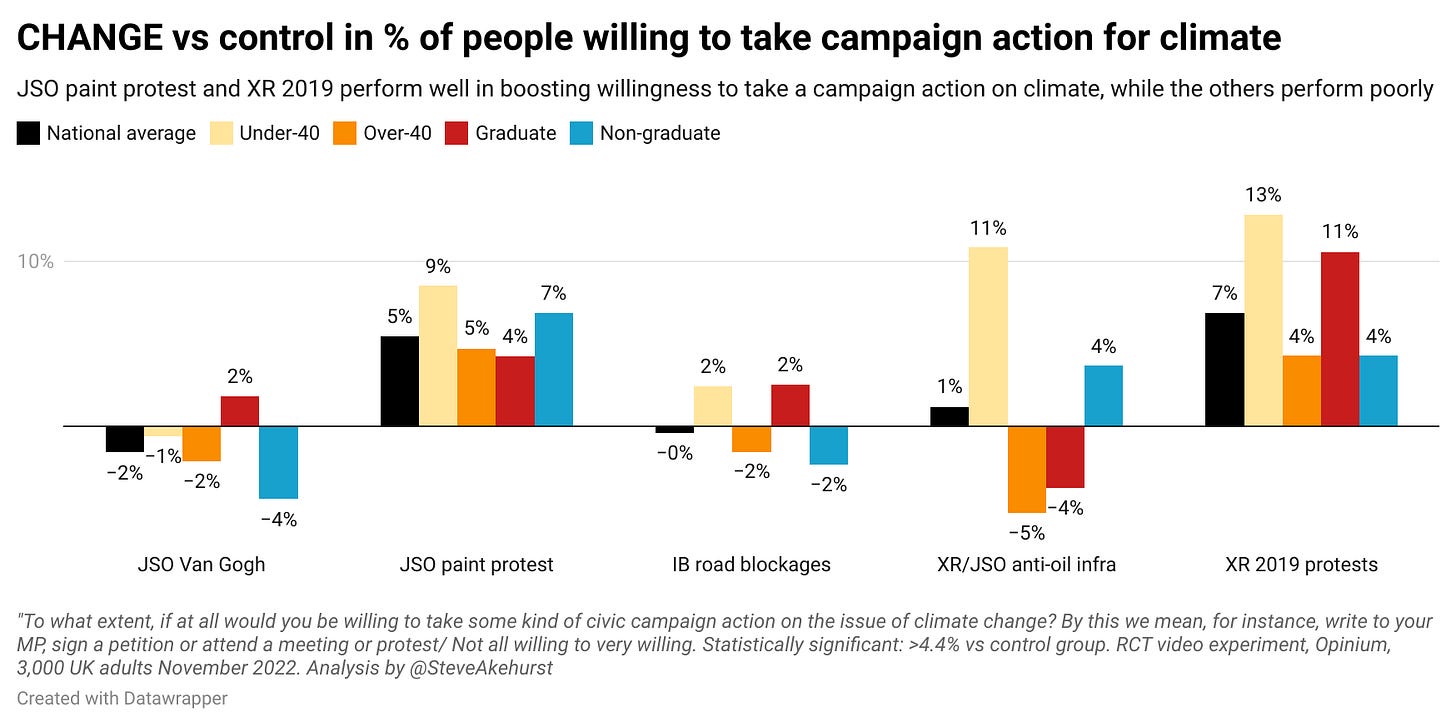

On this, the results are more mixed. As we can see from final tallying, for the JSO Van Gogh action, XR/JSO anti-oil blockages and IB roadblock protests, the answer is at best ‘not a lot’. In aggregate the significant persuasion effects on the first two were actually negative – that is, they marginally made people in this experiment more hostile to climate action, which is unusual.

There is also some polarisation under the surface with these videos: they often converted under-40s or graduates while making non-graduates or over-40s more resistant to climate action. These type of effects are not something we typically see that much of in climate message testing experiments in the UK (as opposed to US, for instance). Given the electoral power of non-grads and over-40s, it seems bad.

However, you can see that two of the videos did quite well: JSO’s paint throwing protest and the 2019 XR protests. In the case of the 2019 XR action, it did really well, moving people across all demographics.

Just to dig a bit deeper, a few metrics on which this plays out:

Reflections: so what?

How should we pick the bones out of all this, and what lessons might be drawn?

In truth we can only speculate, hopefully in a more informed way.

It’s easy enough, I think, to intuit why the Van Gogh and IB road blockages failed. The first was a target that probably appeared random to most people; the second marred by scenes of dispute with ordinary members of the public.I didn’t test it but we can imagine the Canning Town protest would have fared similarly.

In this sense the anti-oil terminal video not working was surprising, as it felt like it picked a clear and tangible villain and limited direct disruption to ordinary people. Perhaps the anti-messaging was effective at a time of high energy prices, or the road blockage element evoked images of other unpopular actions.

The whole set was only saved from washout, really, by JSO’s paint protests and the 2019 XR action.

The former did better than I expected. Why? It’s hard to say but maybe because it’s anti-government, maybe because the messenger heavily uses appeals to expert opinion. Or perhaps because there’s something compelling about the spokespeople themselves.

It’s the 2019 XR video which is really worth focusing on, though. Because we know from polling that the 2019 actions probably did play a role in pushing climate up voters’ agenda in the real world, and it does very well again here.

I’ve long had a lame joke about XR that “I prefer their earlier stuff”, but oddly it does now seem a legitimate line to take! If the essence of it could be bottled then it would be pretty valuable.

What is that essence, exactly? It’s worth noting there’s a small chance of a methodological quirk here: that action was the longest ago and thus maybe the decay effects of any impact with the control group are greater. But I don’t think that’s the case - there’s no signs in the wider data set consistent with that theory.

More likely it’s the carnival atmosphere of the 2019 action doing a lot of the work. It was larger and had an array of voices. The news package also had vox-pops of ordinary people speaking in favour of it (including a cabbie), alongside the criticism, and in general the whole media framing was softer. Overall, it was just a bit ‘nicer’ and less aggy.

This probably isn’t a comfortable thing to learn, given the stakes, and it’s hard to know how much ‘of its time’ it was. Likely it’s hard to replicate (maybe that’s why XR stopped). But the evidence stares up at us nonetheless. I’d be interested in any alternative take on it!

In terms of guard rails for direct action then, I’d say the following stands up:

Don’t do anything that can provoke confrontation with ordinary people

Don’t do anything that seriously inconveniences ordinary people, or seems to. As an ancillary, we can probably say with confidence: avoid road blockages.

If picking a target, make sure its one that is tangible and already unpopular (ideally government) rather than too clever by half (probably what went wrong with the Van Gogh action).

The support or involvement of working class voices (and accents) is probably important, as are experts generally (even more so if built on real-life experience).

Again, I appreciate the limitations this imposes and its advice far easier to give than to heed. Activists have the eternal dilemma in staying within these boundaries but being risque and new enough to earn media attention. Polarising actions please internet algorithms and travel further quicker, creating the appearance of success.

Nevertheless, the evidence is what it is. The above is fairly obvious but they’re rules supporters of direct action can sometimes tie themselves up in knots creating intellectual justifications for ignoring.

Because successful and influential stunts are genuinely hard to pull off, activists (understandably) occasionally fall-back on the idea that, basically, all publicity is good publicity. If there’s one thing this experiment proves, it’s that that this isn’t true.

Of course, it’s also perfectly legitimate to cut public attitudes out of a theory of change and say they don’t matter, or they’re collateral damage. Some supporters of strike action have argued this recently. While I disagree, there’s an admirable honesty and strategic clarity to this. The worst place to be in is wanting to bring the public along but unwittingly doing things that leave them non-plussed or alienated.

There is a glide path to raising public support for climate action via direct action protests, but its seemingly pretty narrow – and, honestly – sometimes a bit random. Basically: it depends, and we still have a lot to learn about when and why. In the meantime, ‘don’t do stupid shit’ is a decent rule. I won’t wait by the phone for anyone to invite me on television to say something as laboured as that, but hopefully it’s useful nonetheless.

~ @SteveAkehurst

*The full results are here, please let me know if you have access problems. If anyone would like the data file (SPSS), DM me on Twitter.

**I funded this experiment out of a small underspend in my budget at work (ECF/GSCC). Given the sensitivity of this area, I should point out again that everything here is entirely my views, reached and published totally independently, and is not necessarily shared by my employer, any of my colleagues or anyone connected with them! So if you are annoyed at anything written here, please be annoyed at me and nobody else.

I'm confused.... This article talks about the popularity of the 2019 protests, and I am making the assumption here that that's referring to shutting the city down for 11 days.....

If that is what's being referred to; how do we conclude the guardrail 'avoid road blockages' advice? With 'confidence' even?

I think there is a wonky undercurrent here though, and maybe its because I'm not in the UK working on the 100 days campaign.

But why is there this undercurrent implication that actions being popular with the public equal success? I understand 3.5% needs to be mobilised; but I dont think the actions that the public 'approve' of equate to those people mobilising and joining in.

Also, if you genuinely acknowledge and understand the emergency we are in, someone stopping a road about it does not turn you away from seeking climate justice. So those people who were 'turned off' by the actions were probably never actually 'on'. Moreover, with the 3.5% rule; that still means 96.5% of the population have not moved into action and dont need to. So mainstream popularity isnt needed to get those changes we need.

Only just found this research (thanks to a Guardian article). There are some minor surprises, but generally fits with what I suspected as a long time Greenpeace trouble maker, who is in turn troubled by JSO and IB. However, and this is the big one, JSO defend themselves partly by saying they get TV coverage whereas Greenpeace et al don't any more. Is bad publicity worse than no publicity? The results above suggest maybe so.