Getting to know Labour’s new electoral coalition

Divided on identity, united on economics

At some point in the next eight months, British politics will be recast. Elections bring to power not just new politicians, but entire new narratives which shape the way we are governed and how we make sense of ourselves as a country.

This is especially true in change elections. If Labour wins the whole sociology of our politics will shift in subtle but important ways. The mood of the nation will be interpreted by a different web of politicians and apparatchiks, all refracted through a new set of inter-familial squabbles and ideological predispositions.

In this effort a different set of voters will come to power, too. If Labour’s victory is as healthy as the polls suggest, the party’s electoral aims will mostly become holding what it has. This will bring into focus numerous voter groups who don’t currently command much attention in Westminster.

In its minds eye, when much of SW1 sees a swing voter it currently sees some approximation of a Con-to-Reform switcher: GB News watching, older, with strongly held socially conservative views. Since 2016, our entire politics has orientated around this pen portrait.

But if Labour governs this will have to change. These voters will still matter, but less than before – because there will be vanishingly few of them inside the new government’s electoral tent. Importantly, that same tent will look strikingly different to 1997, and even the 2000s, too. This will matter to policy outcomes.

So who actually makes up that coalition?

To get at this, we can mostly use long-running British Election Study (BES) data. Although its latest wave is from last year, recent polling suggests the composition of Labour’s vote has been pretty stable over time.

The basics

There are five main groups, then, which make up the bedrock of Labour’s poll lead:

Conservative to Labour switchers. These are particularly vital in Red Wall constituencies.

Lib Dem to Labour switchers. Especially crucial in Blue Wall seats.

DNV (‘did not vote’ in 2019, despite being eligible) to Labour. Voters who didn’t want to vote for Corbyn but couldn’t bring themselves to vote for Johnson.

SNP to Labour switchers, especially vital to Labour’s recovery in Scotland.

The Labour base – those the party has retained since 2019.

Each group’s vote recent history is here if you’re interested.

Some demographics

If we look at the basic demographic profile of this coalition below, a few things jump out.

Firstly, while technically there have been big overall swings in support among older voters, much of this has been from Conservative to Don’t Know or, more latterly, Reform.

Conservative to Labour switching looks an altogether more normie affair; more Gen X than Boomer. They are disproportionately home owners with a mortgage, exposed to recent interest rate rises. They are also the most likely group within Labour’s coalition to say they have struggled financially in the last year.

You see a strikingly similar profile with SNP to Labour switchers. We’ll get into this in more depth later, but essentially these are groups for whom cost of living concerns trump everything else right now.

Elsewhere, Lib Dem to Labour voters look a little as we’d expect: higher income and higher educated.

It's this last point I want to dwell on for a bit. Comparing to 1997, there are several differences between Labour’s vote now and that which gave it its ‘97 landslide; more renters, ‘boomerang kids’, more middle class voters. More non-white Britons.

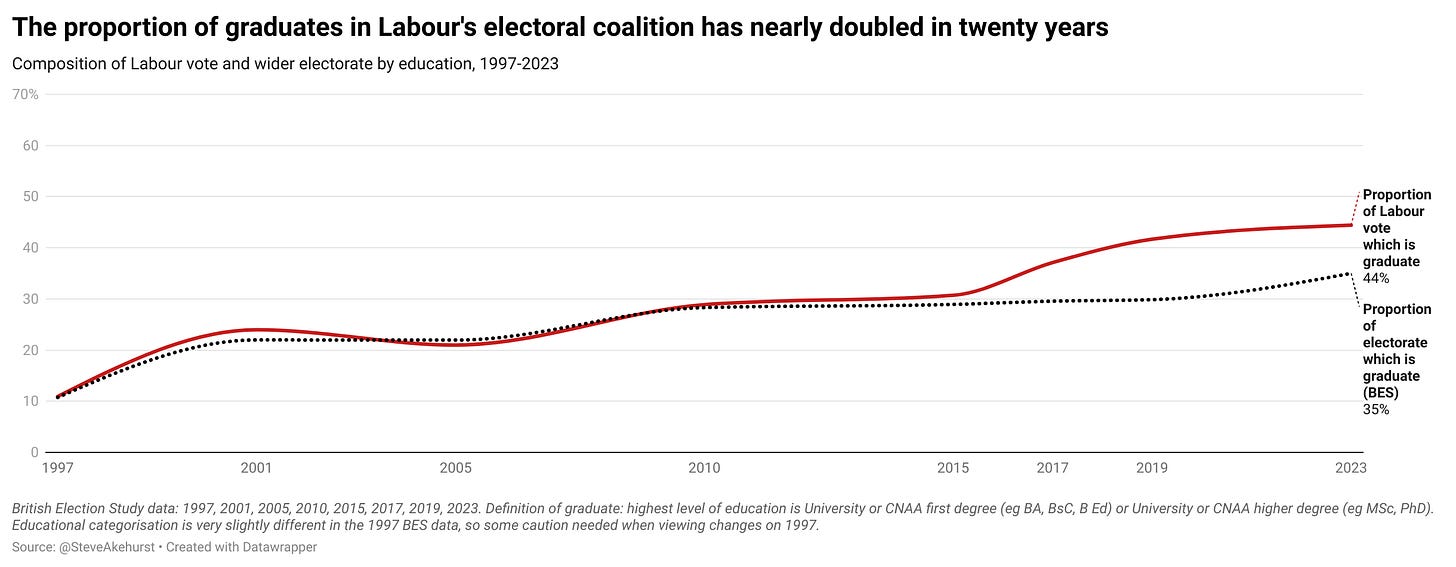

But none of these comes close to differences on education. The massive expansion of university participation, combined with educational polarisation in voting patterns after Brexit, have combined to totally transform the Labour vote to a striking extent. Around 44% of the Labour vote is now university graduates, nearly double twenty years ago. They are 34% of its vote in the Red Wall, an astonishing 51% in the Blue Wall and 37% in SNP held Scottish seats.

Why does this matter? In short because graduates tend to be different kinds of voters to non-graduates, in multiple ways. Chief among these is that they are just more socially liberal, as the work of Paula Surridge, Maria Sobolewska and Rob Ford has shown. This flows through to their views on things like immigration, law and order, positive discrimination and so on.

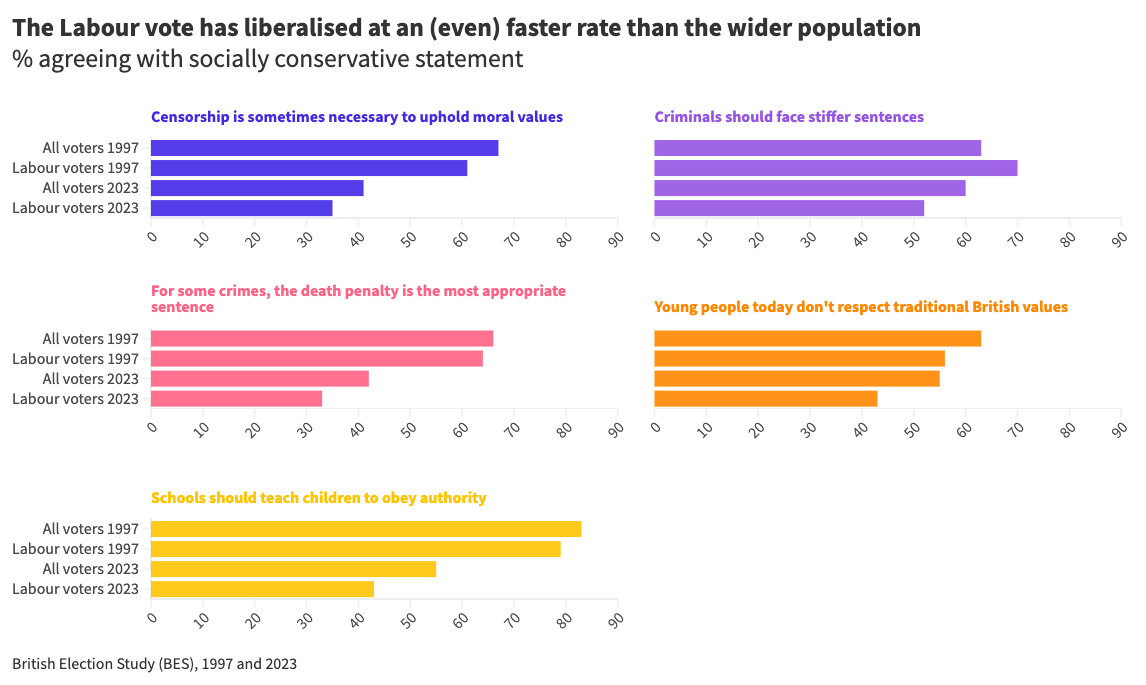

The explosion of higher education is a large part of why Britain has liberalised so much in the last two decades, something Matt Holehouse recently documented. But as the below graph shows, that trend is especially pronounced among the Labour vote. On BES’ favoured predictors of liberal/conservative values, the average Labour voter in 1997 was about as liberal as the average Brit (64% supported the death penalty!). Now they are reliably 8-10 points more liberal.

It's here where danger lies, though. This is an unfinished revolution. There are still many voters with more socially conservative views - primarily though not exclusively non-graduates - left in Labour’s coalition.

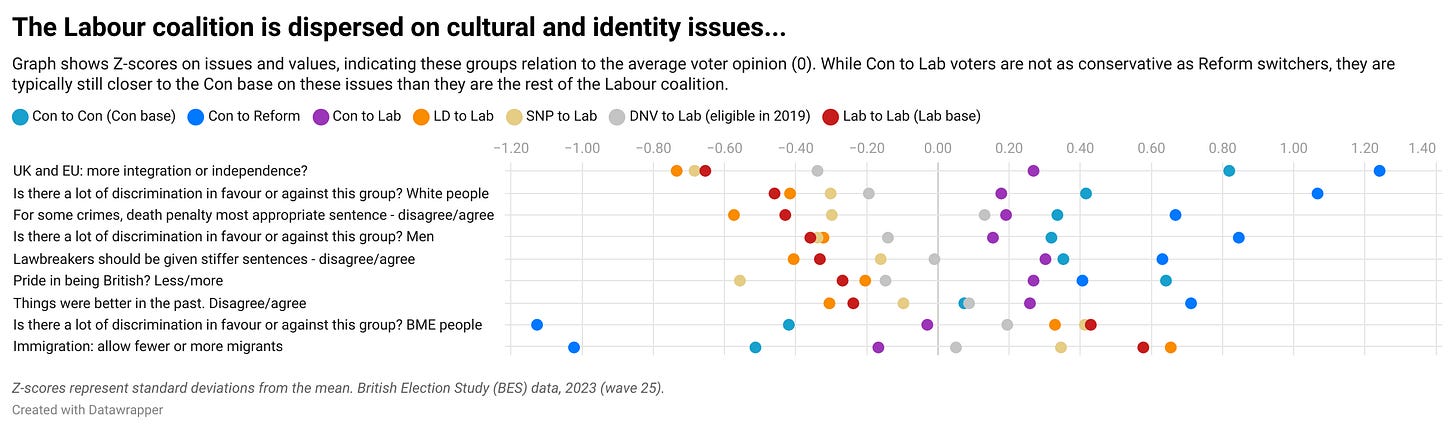

As a result, the party finds its voter base more divided on social and cultural issues than before. We can see this below, when we plot the attitudes of different parts of Labour’s coalition in relation to the average voter. Look for the purple, orange, yellow and red dots - those component parts the Labour vote: they are much further away from each other on culture and identity issues: the EU, immigration, cultural nostalgia.

Importantly, this does show us that Con-to-Lab switchers are not as socially conservative as the Conservative base, or Reform voters. The fact they wear their social conservatism more lightly is part of what enables them to switch when bread-and-butter issues become important to them. That said, they still do remain closer to the Conservatives on identity and cultural issues than they do to the rest of the Labour coalition.

This would not leave Labour much room for manoeuvre on these kinds of matters once in power. If they become salient and a Labour government is seen as being too inattentive to them, Con to Lab switchers may be tempted back.

Likewise, though, it probably cannot ‘do a Denmark’ and tack aggressively to the right on these things. If it becomes too overtly authoritarian, it risks losing more of its vote – back to the Lib Dems or to the Greens - than it did in the New Labour era, when it could more safely gamble them away. These are not the same voters as the terminally online progressives who get annoyed at the mere hint of a flag. But there is a limit to where they will follow.

That is the other thing worth noting about socially liberal graduate voters: they tend to be younger, and younger voters are far more transactional and less attached to political parties than older generations.

All of which justifies the caution Labour has shown on these issues.

There are other areas where caution alone is a risk, though. Take Net Zero. If the transition to electric cars or heat pumps is botched amid Treasury penny pinching, cost-sensitive Con-to-Lab swing voters could easily become dragooned into an anti-Net Zero cause they currently have little interest in. Yet if those policies start to become watered down or ditched, or a picture builds up of Labour as underwhelming on climate, a signal will be sent to other softer parts of its Blue Wall vote in particular, leaving an opening to the Lib Dems and Greens.

So what?

All of this makes for a volatile mix: a coalition more fickle and disparate than before, united principally by the cost of living crisis and a desire to see the back of the Conservatives.

What, then, might keep that together if Labour wins power?

In my view, we can think of there being roughly three axes to how voters decide how to vote, all differing in importance at different times: how close they view the parties to them on cultural issues; how close to them they are on left-right economic matters. And then how competent and trustworthy they view them as.

It's this last factor which has holed the Conservatives below the water line this Parliament. It can’t be understated. For this reason, at least at the start, the diligence and decency of Starmer as Prime Minister – turning down the chaos and getting politics out of voters lives for a bit - could go a long way.

If the Conservatives pick somebody mad as opposition leader, that also helps a squeeze message.

But it will probably need more than that, over time, not least because of how the media works. Labour would need to set the agenda and draw dividing lines that disrupt the opposition Conservative’s own attempts to build its coalition.

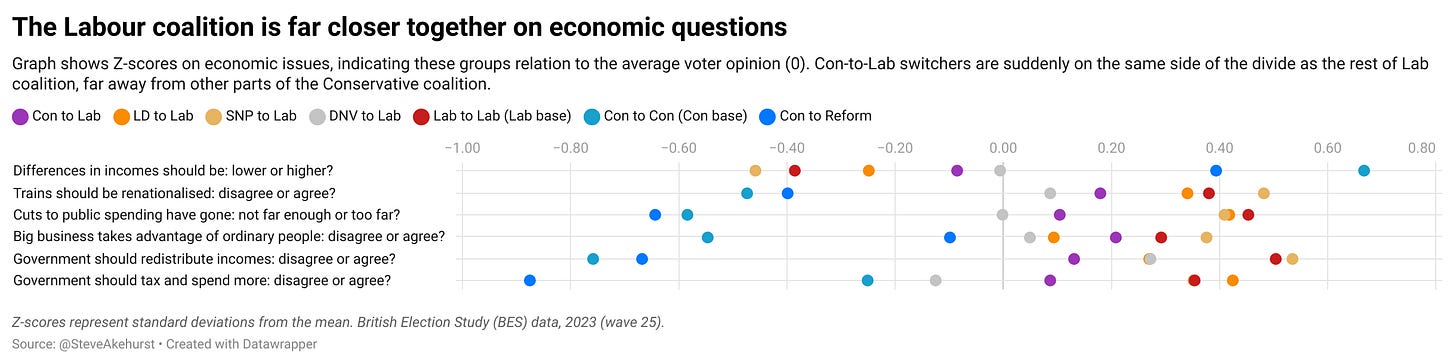

And it’s here where its saving grace is economics, I think. Just as on that last graph we could see Labour’s voter blocks separated on identity, below can see them much closer together on economic values.

Crucially, this compactness is much more the case than in 1997, when the separation between voters Labour gained between 1992 and 1997 (the blue dots below) and its base (orange) was primarily economic.

‘Governing as New Labour’ thus meant continuing reassurance to middle class voters about state largesse in particular, something Blair was instinctively attuned to.

Today, it would mean vigilance and continued caution on culturally divisive issues, finding approaches that can carry Con to Lab switchers even if never satisfying Reform type voters.

That leaves an opportunity on economic concerns. Of course Labour in power cannot go too far. It can’t afford a Truss style market meltdown or start to look excessively punitive or zealous. But once in government it would have more space than it thinks. Outbursts from critical CEOs or frowning Times editorials will not have the same punch with voters as before.

If the objective is to maintain the salience of economics, what kind of issues could it foreground? If I knew the whole answer here I’d be richer and smarter for it. But some ideas: private rented sector and leaseholder reform; workers rights; renationalisation of the railways; a tax on the super wealthy to fund the NHS; borrowing to invest in infrastructure; a big push on clean energy under the banner of energy independence.

All things Labour already supports or has flirted with, but not made the centre of its pitch for various reasons. And all things the Tories would struggle not to oppose in opposition, helping shape these as conflict or dividing line issues.

That approach carries risk, of course. But a far greater one is that, once in power, the party gets swallowed up by the same forces rocking social democratic governments elsewhere: divisive arguments over immigration and a general voter mood of anti-incumbent impatience and malaise.

There is still a long way to go in this Parliament. Things will tighten. But if Labour pulls off a victory, it will inherit the same challenge as the Conservatives did in 2019: holding together a broad but potentially fractious electoral coalition, mostly transactional in their attachment to the party, spanning Red and Blue Walls. It will quickly have to start thinking about how it meets that task and wins the election after that. It won’t be easy – but it won’t be impossible either.

~ @SteveAkehurst