Viewed from one perspective, understanding next week’s UK general election is a pretty simple affair. A deeply unpopular third term government has frittered away its reputation for trust and competence and is now losing votes in all directions. Polls suggest a broad tidal wave will sweep them away, helping Labour rebound in the Red Wall and Scotland.

These basic facts will get you most of the way there, but not all. A small but distinctive part of next Thursday will be what’s happening in a particular set of once safe Conservative seats - mostly to be found in England’s leafier commuter towns or the outer reaches of major cities.

They are places like Wycombe, Altrincham and Sale West, Wokingham or the Chancellor’s seat of Godalming and Ash.

These are what I personally would think of as ‘Blue Wall’ constituencies, a term I had the dubious honour of coining here back in 2021. As featured in the FT, they are the focus of some research for a new initiative I’ve set up, Persuasion UK, to study public opinion in the coming years (more here – please do follow us!).

Many of these seats look set to fall to the Liberal Democrats or Labour next week having never known anything other than a Conservative MP. The essential thing to know, though, is that the drift started long before Liz Truss turned up or Boris Johnson broke Covid rules. Whether relatively or absolutely, the Conservatives were going backwards in these seats even when times were good.

What explains that, and what might these seats mean for a possible Labour government?

Working with the excellent team at YouGov, for the first time I’ve mapped these constituencies’ new boundaries to Census data - and conducted polling in the top 50. I ran the same poll in Red Wall seats and nationally to give us a comparator.

You can get the full research on our website, or see your ‘top 50 to watch on election day’ here - but in summary here’s four things I found:

1. Demographic change

One of the fundamentals I wanted to answer was: is ‘Blue Wall’ even still a useful concept? Like it’s Red equivalent, it has become a bit debased as a term, but it also can’t be defined methodologically in the same way (as the great Matt Singh among others has pointed out).

The reason I think the answer is ‘yes’ basically comes down to demographics. It’s a useful idea because it draws attention to the flipside of ‘realignment’ – a kind of voter and place that often gets neglected in political coverage, which the Conservatives traded away after 2016 and will now play a part in their downfall - but more importantly in UK elections for decades to come.

These are more prosperous places, yes, less white too, but above all they have a far higher proportion of university graduates than the Red Wall especially.

They are also notably more mobile, being far more likely to move around as they get older. Indeed if you look at the areas which saw above average increases in rates of internal migration between 2011-2011, you see a lot of further out Conservative-Liberal Democrat battleground seats particularly.

As this university-share of the electorate rises and/or fans out across the country, it’s stored up problems for the Conservative party.

2. A values disconnect

The reason political scientists in particular wang on about education is because it’s strongly linked to values in one form or another. As I’ve argued before, graduates are different types of voters.

This leaves its mark on Blue Wall seats. These places tend to care about things the Conservative party used to talk a lot about under Cameron but have since stopped, like climate change or housing.

More than anything, though, the Blue Wall seats tend to have more socially liberal views, again mostly driven by higher rates of university educated voters.

And here we now see a serious value disconnect has opened up between these seats and the Conservative party. On social issues, they place the Conservatives far to the right of themselves, which is not the case in Red Wall seats.

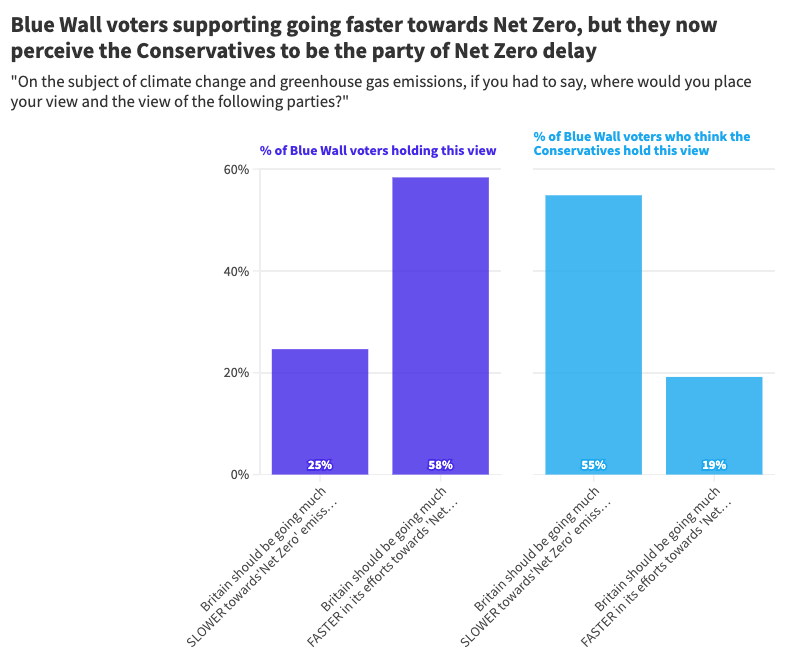

This is evident in attitudes to immigration, Net Zero and Brexit (though there is even now a plurality for ‘Rejoin’ in Red Wall, which seems to have gone under the radar a bit). Climate is a particular own-goal since it’s one of the Conservative’s biggest achievements in government - but recent backsliding has been noticed.

This is all compounding their woes on top of all the usual stuff, I would argue.

3. An ‘anti-Conservative’ majority in the Blue Wall and potential for tactical voting

One reasonable challenge to this hypothesis would be to say, well the Conservatives won these seats in 2017 and 2019 under May and Johnson, post-Brexit realignment. All they need to do is be a bit more competent and recover their position at that election.

This isn’t totally unreasonable. But it ignores two things. Firstly there is the issue of long-term under-performance and slide. Secondly, it ignores that there were many voters in these places who could not vote for Corbyn in particular, so the anti-Conservative vote split.

That is not true this time. Shifts in voting patterns and demographics now not only leaves large mass of voters in these seats willing to vote for a progressive party, but – given the at-times intentional trolling of liberal minded voters by the government in recent years – one highly motivated to vote against the Conservatives.

Indeed, it’s really striking that in these places the Labour and Lib Dem voters are close to interchangeable and highly efficient. When you apply a squeeze question, you get massively high rates of intended tactical voting, unlike in the Red Wall when things tend to be stickier.

This is one of the reasons I think losses in these seats may be deeper than some polling suggests, and why the Tories may continue to under-perform here relative to national swing.

I would argue this is not a sustainable position for the Conservatives to be in these seats. You can skate by sometimes but in the end median voter theory catches up with you.

That leaves the party with three strategic options. The first is to return to a Cameron style approach to ‘detoxification’ of the brand, trying to peel some of these voters back into their coalition. The other is just to write these places off as collateral damage.

The, third, I suppose, is to muddle through. Stay in roughly the same place but hope the anti-Conservative vote fragments under a Labour government, the Reform vote gets squeezed amid anti-incumbent sentiment and the Conservative’s sneak through the middle. That is unlikely to work albeit not impossible, as we’ll see below.

4. Dilemmas for Labour and the Lib Dems

Though Blue Wall seats are commonly associated with the Liberal Democrats, on strict definitions at least Labour are set to win as many seats here as the Red Wall. In doing so they will inherit the Conservative’s strategic dilemma of balancing the two.

In this regard the differences between Blue and Red Wall voters somewhat manifests a broader fracture in their voting coalition I’ve written about before, between slightly more socially conservative and liberal voters.

As I wrote about, this makes it dangerous when cultural issues become salient on which different bits of Labour’s coalition disagree. The good news is they tend to be united on economic issues.

If I were being hyper critical, the blind spot Labour occasionally has is to think more liberal minded voters are only to be found in Hackney North, or other safe Labour seats. They are not. They’re spread out across a whole bunch of seats the party is set to win across the south of England in particular, and they are swing voters.

They are also very transactional - and not that attached to Labour, as we can see below. Many more Labour voters in Blue Wall seats are happy to switch to the Greens or Lib Dems next time than in the Red Wall. Fretting about leakage to Reform also looks a red herring.

Right now, that coalition is held together not just by anti-Conservative sentiment but by the salience of bread and butter economic issues. Unless it wants to write off these places (a perfectly legitimate option, incidentally), it needs to keep it that way.

For the Liberal Democrats, meanwhile, the issue of Brexit arises. For good reasons, Labour in government will be doing its best to avoid the topic. Yet in our research we found important parts of the Labour vote, especially in Blue Wall seats, might be moved by a ‘Rejoin’ position or similar. There is an opening there for the Lib Dems. But that itself requires them to square it with their party’s resurgence in more Leave voting parts of the South West.

So what?

Above all, this last point should remind us that these dilemmas are not just of interest to psephologists or political anoraks.

How parties navigate these fault lines and compete for votes in different places has significant implications for policy in a whole host of areas – and by extension people’s lives.

The rise and revolt of liberal England, then, does not just influence who we are governed by in the coming decades, but the kind of country we will live in during that time. Any party that under-estimates it will likely get what they deserve.

~ @SteveAkehurst

~ @Persuasion_UK

---

Full research is here.

If you found this in any way useful or interesting, please can I ask two things in return:

Please follow @Persuasion_UK on Twitter/X (I have funder reports to fill out you know!)

Do share this post on Twitter, since Elon has an algorithm suppressing Substack these days!

Thanks again to the brilliant team at YouGov for their help on this project, in particular Beth Kühnel Mann.